So first of all, the value of public speaking I cannot emphasize enough. I started speaking at 23 from stage and at 23-years-old, I didn’t know what I was doing. I was actually pretty terrible at it. I was thrown in the deep end and I can’t even swim and it was like being thrown into the water and I would sink, right? I was terrible at it but that just gave me the resolve to do it much better. And when I say I was thrown in the deep end, when I actually had my first speaking gig, not only was I going to speak at a conference from stage but I was also going to keynote the conference, share it, and do a post-conference workshop, which was 3 hours long. It was a small audience, fewer than a hundred people, but it was terrifying.

Now we talked in the episode a bit about how to get over the fear of public speaking and that it’s kind of a misnomer that it’s the scariest death—it’s not at all, it’s a myth. In any of that, if you were to just stop there with a terrible speaking experience, you know nobody came to me afterward and said, “Wow! That was the worst speaking I’ve ever seen!” No, I just knew that I was not a very effective speaker and that just gave me the resolve to do it better and better. The funny thing about being a speaker, at least in the internet marketing space, at the time when I started, all the different conference organizers poached each other’s speakers. I started speaking for IQPC and then IIR started calling when they saw that I had been a major speaker at this one conference where I’ve shared and done a workshop and general sessions in. I started getting speaking gigs from IIR and then another conference organization contacted me from seeing me, probably on various brochures for either or both of those organizations, and I just went on and on and I said “yes” to everything. I was a prolific speaker and I just got better and better over time but you don’t have to keep beating your head against the wall in order to get excellent at this. You could learn some skills.

Professional or public speaking is a learned art

Professional or public speaking is a learned art so if you apply some simple principles that are really not that scary and are easy to learn, you‘ll be amazed at the progress you make. So let me just share with you a few different ideas. First of all, getting the audience engaged. The rule of thumb is that at least every seven minutes, get them to raise their hands, or turn to a neighbor to say something, or ask a question. Any kind of audience engagement, where it’s at least once every seven minutes, is going to keep people just engaged and with you rather than you just kind of lecturing and people are falling asleep, so that is a critical one. Another is to pay attention to your body language and don’t just be unconscious about it but be really intentional. For example, in this episode, we’re going to talk really briefly that open palm is better than closed palm and what that means is, when you have your palms up or exposed, that is a good thing because that makes you look less threatening and less like you’re telling people what to do, whereas when your palms are down when you’re talking or giving people directions. Even worse is if you’re pointing because that’s where you’re basically in a “one-up” position from the audience and that’s not the way to build rapport at all. Also, be very intentional if you are going to curse from the stage.

Don’t just let the F-bombs slip out and be very intentional about what you’re trying to achieve. If you are using cursing as a pattern interrupt like Tony Robbins does, that works. A pattern interrupt is an NLP technique, neuro-linguistic programming, and it works. It interrupts their pattern, gets them out of a trance, and into a state of receptivity. Now, some people will bristle at hearing an F-bomb or whatever swear word you’re using but the point is, you’re not trying to get everybody on side. In the entire audience, you’re going to have frowny faces, as Robert Allen likes to say, as well as smiley faces, and you’re speaking to the smiley faces, and not to the frowny ones. There is always going to be a percentage of your audience who just doesn’t like you and that’s okay so speak to the smiley faces and don’t worry about the frowny faces or try to convert them or convince them.

You are not there for them and they are not there for you so that, I think, is a really powerful way to think. Also, if you can think of speaking as a story arc and you are taking people on a journey with you—facts tell, stories sell. I just can’t emphasize enough that storytelling is a critical piece to your public speaking, your negotiation, or your convincing and building rapport. If you only just kind of stick to the facts, people would get bored and would lose interest. Take them on a journey, as there is a story arc that’s involved here, and have open loops that you return back to later by not immediately closing them one after another because keeping some intrigue going is really powerful.

Storytelling is a critical piece to your public speaking, your negotiation, or your convincing and building rapport.

What else do I want to say here? If you can maybe move around the stage and not just hide behind in the podium is also helpful. Now I know in this episode, Michael talks about using a style that works for you as there are no hard and fast rules but I find that a podium can be a crutch so I try to get away from the podium. I try to get a level-ear mic—a lapel mic—instead of having to use the mic at the podium so that I’m free to engage the audience. I might even go off stage—I’ve done this and it’s very impactful. Go off stage and get amongst the audience and then go back on stage. It’s just an amazing way to break patterns, interrupt patterns, and to build rapport. Putting your hand on somebody’s shoulder, as you’re speaking to him or her and the entire audience, is a different way to engage. That way, you can show that you’re not just there to teach, take notes, and so forth. It’s really about engagement and rapport-building so I hope these tips are useful. It’s an incredible skill that is going to pay dividends for the rest of your life.

When I ran my agency, Netconcepts, for 15 years, it was the most powerful marketing strategy out of every strategy we had in place. I got so many new clients out of my speaking gigs that have just, hands down, driven the most business so you have to start somewhere. If you think about, “Alright, I’m going to get past my first speaking gig and then I’ll never have my first speaking gig ever again. I’m going to succeed or fail or whatever,” but failure is just a step towards success. What matters is, you get out there and you do it. Get more gigs and then go from a breakout speaker to a keynote speaker over time. Do more and more speaking gigs because practicing in the safety of your own home is only going to get you so far—you really have to be in front of an audience in order to learn. I’m not discouraging practicing behind closed doors–definitely do that too—but get as many gigs as possible and then try to get to a keynote speaking role over time as you get better and better because that means having to speak to thousands of people.

I think I’ve had, 3 or 5,000 people—the largest audience I’ve spoken to. I’ve also spoken on TV and radio where, potentially, you have a massive audience but you don’t feel really scared about it because you don’t feel that huge number of eyeballs on you when you’re in a live stadium-type environment. So, just get out there and do as much as you can to elevate to new roles in your speaking career. As you progress in your skillset, I think you’ll find that you’ll reap tons of rewards from it. Also, think about treating it as a profession or as a business and not just a thing that you can do on the side. There are such folks as professional speakers. You could learn about speaking by improving and honing your craft simply by going to Toastmasters and I’m not knocking Toastmasters, it’s a great entry point, but if you want to really take it to a whole other level and effectively become a professional speaker or operate at the level of a professional speaker, you might want to consider joining the National Speakers Association. NSA is an incredible place for folks to learn the business of speaking by learning how to hone their craft to top levels and finding the mentor or somebody you can model after to do so. Okay, so I have given you a lot of stuff here. Let’s dig into the episode with Michael Port. Here we go.

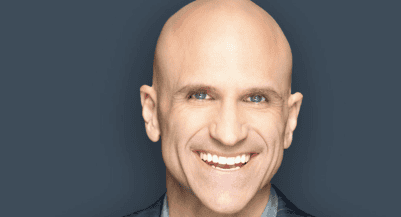

This is Get Yourself Optimized and I’m your host, Stephan Spencer. Today, we have Michael Port on. It is an incredible pleasure to have you, Michael. Michael is a New York Times and Wall Street Journal best-selling author. He’s a speaker, a marketer, a trainer, and he has been an actor. You might have recognized him from such shows on film and TV as Sex and the City, Third Watch, All my Children, Guiding Light, Central Park West, 100 Centre Street, The Pelican Brief, Down to Earth, Last Call, and The Believer. He has six books: Book Yourself Solid (available in multiple editions), Beyond Booked Solid, Steal the Show (it’s his newest one!), The Contrarian Effect, and The Think Big Manifesto. He actually took Book Yourself Solid and created the whole framework and program around it. He franchised around the world. I actually met one of his trainers, Matthew Kimberly, a really smart guy in one of my mastermind groups that we’re both in, and that’s how I learned about you, Michael. Book Yourself Solid has stuff in there about authority marketing, sales cycles, lead nurturing, info-product marketing, various pricing models-I believe there are 12 of them that you go through- and how to do outreach. We also have the Michael Port Method that is all about public speaking and you also have a public speaking course online called Heroic Public Speaking at www.heroicpublicspeaking.com. We’ll talk more about that course and so forth in just a minute but let’s dig in, first of all, and talk about speaking as performance.

Sure! To affect people, we need to reach them emotionally, intellectually, and physically. And, information really touches on just one of those three. We can reach them intellectually with information but often we reach them emotionally and physically through the experiences that we create in the same space. Performance just doesn’t apply to giving a speech. I mean, Shakespeare said it first. He said, “All the world’s a stage,” and if you think about your life, it’s made up of high-stakes situations, and how you perform during those situations determines the quality of your life. If you fall flat when the spotlight is on you then not much happens but when you can shine when the pressure is on, then you can do big things in the world and that requires performance.

So high-stakes situations include everything from a job interview, to a negotiation, a sales pitch, meeting a potential referral partner for the first time, or maybe even meeting your future in-laws for the first time. These are high-stake situations that require you to be able to manage how you feel, how you breathe, and what you’re trying to do. Everything you say or do tells the world something about you and if you are going to get people to think differently, feel differently, or act differently, you want to make sure that you have an objective that you can pursue. That’s what actors do—they pursue objectives and the way they pursue those objectives tells you what you need to know about that character. The same thing is true in life—how you pursue your objectives will tell you who you are and what you stand for.

And I’ve heard the expression, “Facts tell, stories sell,” so when you are presenting either from the stage or in a high-stakes situation, whether it be a negotiation or meeting someone important for the first time, it’s important to incorporate storytelling into the conversation so you’re not just spouting out facts. You’re swaying people and getting them on the side because you have compelling stories, you have a story arc, and so forth. How do you recommend people to incorporate story arcs and storytelling into their presentations?

One of the first bullet points you’ll see in an article about public speaking is to tell stories. Of course, we want to make sure that we insert one more word and that’s “good” because we want to tell “good” stories and not just stories for stories’ sake. We don’t need to open a presentation with a story. It may be very effective but it also may not be if the story is not very compelling. This idea of storytelling just for stories’ sake is something that I think we need to recognize so we don’t get in the habit of just looking for stories to tell, thinking that it’s going to make all the difference in the world. But when we do identify stories that, we think, serve the promise of our message—because any time you’re speaking to a group of people, you want to make sure first that you clearly know what your big idea is and that you can articulate it to them—we then find a way to go and deliver on that promise.

The stories you tell are designed to serve that big idea and the promise that you’re there to deliver so if the story doesn’t meet those two essential elements then we don’t want to use it. I have a process, it’s in Steal the Show, that will help you source stories because one of the things that people have a hard time with is finding them. Sometimes, they say, “I don’t have any stories, nothing happened to me,” but if you look back on your life, oh my God, there are so many things that happened to you that can be so compelling to other people if you know how to identify them and then sculpt them. And the way to sculpt them is by using the three-act structure. There’s a number of different ways to get into it but it is one of the easiest ways to start at sculpting and molding a story. The three-act structure is Aristotle’s three-act structure and it is the structure of most plays and films because when you tell a story or you tell a joke, the first act always offers us the exposition. These are the given circumstances. It’s what we need to know in order to understand what’s about to happen because if we don’t have enough information, we don’t understand the story and we disconnect from the storyteller.

However, if there is too much exposition and it just goes on and on, we kind of go, “Alright, could we get to the part where something happens, please?” Sort of like watching a French film, where you’re like, “Is something going to happen to this film or are they just going to look at each other for a while?” We get excited and we want things to happen as quickly as possible. Act two introduces the conflict—now that you know the characters, the time, the setting, the place, here comes the problem. That’s the conflict, and then, of course, conflict produces action. Action may produce more conflict. More conflict may produce more action and so on and so forth and the tension builds and builds and builds and builds until you get to Act Three, which is the resolution. And that resolution is, if it’s a fairy tale, everybody lives happily ever after or if it’s a Quentin Tarantino movie, everybody dies in the end and the floor is flowing with blood. So it depends on that particular story and of course, if it’s a joke, it’s the punch line.

The stories you tell are designed to serve that big idea and the promise that you’re there to deliver. Share on XSo, how would somebody get over the fear of public speaking if they haven’t had any experience with speaking from the stage? Or, if they, maybe, presented then had a bad experience? I hear that the fear of public speaking is one of the top fears, right up there with the fear of death, which floors me.

It’s not true, it’s actually not true. It’s one of the things that people say all the time because it perpetuates this idea that public speaking is the worst thing you can do and I think it makes people more afraid. Study shows that the reason why people say they are more afraid of public speaking than death is because they don’t think about death. They don’t have to think about death everyday so they’re not really afraid of it. It’s not part of their frontal lobe on a day-to-day basis but public speaking is. Because every time you open your mouth, you’re speaking in public. So if you have two options right now and let’s just say that, hypothetically, you’re afraid of public speaking but your two options are to either speak for 5 minutes or you die—clearly, most people will pick the former so it’s really just having a false comparison.

The reason that people are so afraid of presenting in front of others is very simple: because they may get rejected. We don’t want to get rejected. I don’t want to get rejected. You don’t want to get rejected. I haven’t met people who want to get rejected. When you’re putting yourself in front of other people and you’re putting your ideas out there—trying to offer a solution to something, trying to get them to think differently, trying to spread some sort of message, or trying to make something happen—and people reject that, it feels like they’re rejecting you. That’s not something that feels very good and we’re afraid of that. Now, when you couple that with not knowing what to do, it just compounds the problem. When people say, “What can I do to not be afraid of public speaking?”

I think the simplest answer is actually learning how to do it. Train. This is a skill that one needs to develop. Just like when you’ve never driven an airplane, you’re not getting behind the controls of an airplane and trying to take it up in the air. I’m not equating public speaking to flying—that it’s just as difficult—but some people may feel it is. It’s something that most of us, unless we have some sort of phobia that is extreme, can be proficient in because we speak all day long. But what we don’t know are the techniques—the stagecraft. We don’t necessarily know how to sculpt content or to tell stories, or to use our breath in a way that’s very powerful, or to use timing, pacing, rhythm, rhetoric, and etc. These are all skills that we can learn so one of the reasons why people have a hard time with public speaking is because they don’t prepare.

Putting slides together the night before or the week before, running them through in your head a few times, and then thinking, “Well, I’ll go off my slides and I’ll wing it.” That’s tough. Now, there are some people who think that they are natural communicators and they’ve got the gift of gab and that they’re good with the jokes so they feel like they can just go up there and wing it because they feel freer and they feel they’ll do a better job. They’ve tried a little bit of rehearsal in the past and they feel like, “I don’t know, I don’t think that really works because I’ve tried it and I felt stiff,” and I think that’s right. I think there’s a reason it happened. If you rehearse a little bit, what often happens is, you try to recall what you were doing during rehearsal and then attempt to repeat it during a performance, and as a result, you’re not in the moment when you’re performing and you’re not connected to the audience and you can’t be spontaneous because you’re thinking about the past.

So, any time we’re thinking about the past or we’re obsessing on the future while we’re performing, then we are, generally, very stiff, uncomfortable, and insecure because we’re not in the moment. Our job is to drive forward to achieve objectives with the audience and if we don’t know our material well, that’s hard to do. We need to know our materials so well that we can throw it away, forget about it, and allow it to come to us organically at the moment. Even if you do the same speech over and over 500 times, it should feel, to the audience, like it’s the first time it’s ever been delivered. Of course, for those people who want to become professionals, this kind of work on speeches is essential. For folks who have no desire to become professional speakers, the amount of rehearsal they give to a speech should probably be proportionate to the stakes at hand.

So for some with a very low-stakes situation, I don’t think you need a lot of rehearsal. If it’s in an environment where you’re incredibly comfortable and you feel like you know that particular information very well, and you can get clear on the structure of the presentation, well, you may be able to go in there without a lot of rehearsal. But if it’s a high-stake situation, if it’s your company who sent you to a venture capitalist event and there are all these people who could invest more money in your company and your job is to get up there and convince them to do that, those stakes are high and just knowing your product well is probably not going to be enough to convince these folks to take action and invest in you. When you are well-prepared and you stay in the moment and allow yourself to improvise at that moment, the preparedness and improvisation, when coupled together, produce authentic spontaneity. Sometimes, people get a little uncomfortable when I talk about public speaking as performance. Sometimes, people think performance is when you’re faking it or being phony in some way.

From my perspective, nothing can be further from the truth. The greatest performers in the world are the most authentic performers. They are the most open and honest performers. They let you see who they are inside and that doesn’t mean they are vulnerable just for vulnerability’s sake but they are open and their good performance is not about fake behavior. Good performance is authentic behavior in a manufactured environment and most public speaking situations, most high-stakes situations, are manufactured environments. Even going to meet your future in-laws for the first time, like I mentioned in the beginning, is a manufactured environment. Everybody is a little bit uncomfortable and your fiancée has chosen a particular place that they feel is going to work really well. The parents have an agenda, you have an agenda, and it’s all manufactured so your job is to be as authentic as you possibly can in that space while going after your objective with the tactics that you believe will be effective.

Right, and let’s talk about those tactics a bit because you’ve created an entire course, an online course, heroic that provides this stagecraft that takes somebody from unconscious incompetence to conscious competence and then to unconscious competence. I watched some of the free video trainings that were just incredible because you went through all these different techniques, tactics, and so forth, and things to avoid like don’t repeatedly touch yourself, your hair, your ear, your nose, or whatever.

Well, you know it’s funny because there are certain things that over time have become normal because a lot of people do it. And then you say, “Well, a lot of people do it, I guess that’s how it’s supposed to be done so I guess I should do it too.” And when you’re performing in any way, you’re making art. Even if you’re, let’s say, you’re starting up a new company, you’re creating something new—that’s an artistic expression. So if you’re giving a speech, it’s a type of artistic expression and there are really no rules that you have to follow. There are certain things that work well and certain things that don’t work well. But something that works well for you may not work well for somebody else and something that works well for somebody else may not work well for you.

So, for example, I’m a very physical performer. When I’m on stage, I use the stage and I move. It’s the way I perform physically and it is unusual in the world of keynoting. A large part of it is because I was an actor so I use my body in a different way than most speakers do. It doesn’t mean it’s the right way to do it or the better way to do it, it’s just my way of expressing myself and it’s going to resonate with some audiences more than others, but you’ve got to find your own style and amplify it. But for somebody else, very little movement could be incredibly powerful and that’s more appropriate for their style and more authentic for their style. It’s important to me that any time I’m interviewed or anytime I speak on this particular topic that I’m clear in that I don’t think there’s one way to do this kind of work and any time we start getting into the mindset that, “Oh, this is right, that’s wrong. This is the way it’s done,” we get a little bit dangerous.

Now, with that said, here’s my perspective on the few things that I suggest that you don’t do because I think that they’re done again and again and are often unnecessary. I don’t think they help you differentiate yourself when you’re performing but if you find that they work very well then you do them. Every once in a while, you know, a performer’s job imparts us to break the rules so I will break my own rule from time to time because I find in that moment, it works very well. For example, one of the things that speakers often do is to look at the ground when they’re trying to remember something and this is in large part because they want to disconnect from the audience in order to find their next thought and are afraid that the audience will see that they don’t know what’s coming next. Now, if this turns into a habit, it can be very distracting for the audience.

Interestingly enough, because you’re looking down, the audience now knows that you don’t know what’s coming next and that you’ve lost the flow—so generally, I say, don’t look at the ground unless there’s a reason to look at the ground. You know, you’ve got to have some reason for doing it. For example, generally, it’s not a great idea to turn your back at an audience so sometimes, when people are giving speeches and they’re using visual aids, Keynote, or PowerPoint, they will turn towards the slide every time they will click the side. First of all, they’ll point the clicker at the slide but that is not actually how the slide advance. It’s not from the slide. It’s from the computer and the clicker has a 360-degree wireless signal so you don’t actually have to point it at the screen. In fact, you want to make that clicker, if you’re using it, almost unnoticeable to the audience so it becomes a part of your hand as opposed to some object that is uncomfortable and that you have to deal.

One of the reasons why I suggest people to use their own everywhere they go, if they can, is because I want them to master the feel of it so that it will just become an extension of their hands. Nonetheless, there is, in one of my keynotes, there was a time where I showed these quotes on the slides and I don’t use a lot of slides, but I showed these quotes from people about different events in history or different famous figures that are hysterical when you read them. One of them is about-what if there’s no need for personal computer, who would ever use this kind of thing? Or, The Beatles will never amount to much, they’re really not a very talented band. You know, those kinds of things. Just to demonstrate a point that there’s a lot of experts out there like me, included, who are saying “I think you should do this and not this, etc.” and are not always right.

So what I did was, I put up those and then I turn my back on the audience and I watched them because I want them to watch them. It’s no longer about me anymore. I want them to look at me while I was looking at the slides and it was about 25 or 30 seconds of silence while they watched but it’s a choice. If we train or if we develop a skill, then we can make choices while we’re presenting rather than coming off the stage, “I don’t know what I did on the stage. I hope I was good!” Because there are a couple of different ways to know the difference between an amateur and a professional, and I don’t mean whether if they get paid because there are some people who get paid and they still are amateurish in the way they approach the work. An amateur will run over time, a professional will not. That’s number one.

And also, a professional knows exactly what happened virtually through every moment of that presentation when they get off the stage because a professional can see themselves while they’re performing. It’s really wonderful—I can see myself while I’m performing, I can hear myself, and I can think about what I’m doing right now, and I can manage what’s going on with the room at the same time so this just comes from hours of doing it. You know when you know your material so well. Like, right now, I’m talking to you but I’m also looking at the bottle of wine and the espresso maker in front of me and I can think about all the different things that are on that table and still talk to you and pursue the objective and try to get my message across and be helpful, etc.

I can think about a whole bunch of things at the same time. You want to try to block those things out but when you’re in a space, often you need to pay attention to those things because if there’s a racket going on behind you or there’s some disruption in the audience and you don’t know it’s there, it could disrupt your entire presentation because the audience is going, “Doesn’t he know that’s there’s something going on over there? This is really distracting!” That’s why we need to be able to manage the whole room and when people talk about “owning the room”, that kind of skill is what helps us own the room.

Yes. I know we need to wrap up here so I just wanted to give our listeners here a taste of some of the things that they could learn just by getting the free training from www.heroicpublicspeaking.com and, hopefully, they’ll go through the paid program. Some of the things that you teach in just the free training, the four videos include: weak language, filler language, cursing, and whether to use that or not, opening stories, body language like open palm vs close palm or pointing, how to engage the audience, how to use contrast, how to avoid the story-telling voice, timing, cadence, pauses, tone of voice, and breaking the rules that we talked about a bit already. There is a ton of really great stuff such as how to use the mic and crab-walking, which I’ve never heard before. So, to everybody listening, you really have to go to www.heroicpublicspeaking.com and sign up for the free training, see several video series, and I encourage you also to sign up for the paid program.

It’s been a pleasure having you on, Michael. It’s been really informative. I think people are, hopefully, seeing the other side of being unconsciously competent at public speaking because the power of that is so incredible. Do you have any last final words or tips or anything that you wanted to share?

Well, yeah. You know, I would stay away from the idea of being good at this. One of my clients called me once, frantic because she got booked to be interviewed on one of the broadcast morning network TV shows that she’s been trying to get for so long and when she got it, she was completely freaked out. She’s like, “I can’t do it. I’m going to cancel. I’m going to tell I have the stomach flu or something,” and I said, “Alright, let’s just chill out for a second, what’s the problem?” She said, “Well, I just really want to be good. What should I do?” I said, “You cannot be good. This is not possible.” And I think she thought I was talking about her—that she’s not good. And of course, I wasn’t. What I said was, “You know, you can, I suppose if you want to.”

I would suggest not going into one of these types of situations trying to be good because that’s a very amorphous idea and that’s about you when it’s never about you, it’s always about them. What you can do is, you can go in there and try to be helpful. And, if you know your material, if you’ve done your homework, if you’ve prepped them well, and there are all sorts of technical aspects of being interviewed that are important to understand, well then, all you can do is be in the moment and try to be helpful by answering the questions in the way that you believe is relevant to the audience. Some answers will be more relevant than others. Sometimes, you’ll trip over your words a little bit here and there, and sometimes you’ll even forget where you were and you’ll say, “Wait, what was I saying?” and nobody will have any problem with any of that if you’re helping them in the process.

So, good is definitely the enemy of great and just trying to be good, I think, is a huge mistake. Being helpful, adding value, aiming for excellence—those are all great ideas.

Yeah, people will go, “Oh my god! You’re so good, that was so great! Thank you!” but you’re not going for that approval of being good. You’re going to try to be helpful and that’s what produces a praise, an applause, or a profit that you want to produce from that particular situation.

Thank you, Michael. This was a pleasure. We’ll catch you on the next episode. I’m Stephan Spencer, your host of Get Yourself Optimized.

Important Links

Connect with Michael Port

Tools/Apps

Organizations/Companies

Books