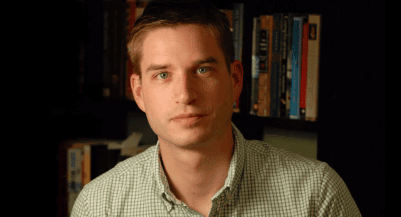

Welcome, Cal! It’s great to have you!

Sure. Thanks, Stephan!

Let’s start with what makes Deep Work so valuable because if we block out time, if we eliminate distractions, and so forth, of course, we’ll be more productive, but it’s kind of an exponential gain from my understanding.

Yeah. I mean, it is the overlooked skill right now in our economy. The terminology The Economist used was, “Deep Work is the killer app of the knowledge economy,” so I like that phraseology. Let’s think about it as the killer app. If you can do this, you can really dominate. Now, why is that true? The ability to really learn complicated things fast is very important in the ever-changing 21st century. The amount and quality of work you can produce sort of per unit time working with deep work swamps what’s possible with the stand of their type of semi-distracted work that almost every knowledge worker actually does. If you are a deep worker and if you’ve embraced a deep lifestyle, it’s like having the superpower that almost no one else has.

Right. How do we develop this skill because it is kind of a learned skill, right?

And that’s crucial to understand and it’s often misunderstood, which is the ability to perform deep work well is a skill that must be trained. It’s like playing the guitar-something you wouldn’t expect to be good at, unless you actually practiced and trained for a long period of time. It’s important to emphasize that because a lot of people think about deep work more like a habit, such as flossing their teeth-something they know how to do and they just feel like they should make more time to do. A lot of people say, “I know how to concentrate,” or “Yeah, I’m probably too distracted, I should probably put aside some more time and concentrate more.” That’s not how it works with deep work. If you haven’t really practiced and trained to set up your life to support deep work, what you’re doing is really not true deep work when you set aside time to concentrate so it’s good news and bad news. The bad news is, you’re going to have to train this before you start to get the benefits. The good news is, if you stick with this type of training, the benefits can be profound.

Right. How do we get to this kind of a ninja skill level? I mean, obviously you’re going to have to invest some time, effort, and energy into developing this skill. Do we just have to go climb a mountain and meditate for six months? What’s the process?

Yeah, that would be a useful way to do, I suppose-six months on the mountain-but even that might not be successful. At the high level, there are two different types of training and activities that are required to really master the skill. One type is active training activities, so these are things you can do that actively stretches your ability to concentrate, just like lifting a heavyweight might actively increase the strength of a muscle. The other type of activity, which is important especially today, are passive training activities.

These are about actually shaping your lifestyle in a way that is conducive with high concentration so to follow our fitness analogy, this would be cutting out junk food, getting enough sleep, stopping smoking, and the type of activities you would do to take care of your body if you want to get more serious about athletics, you have to do similar things to your cognitive life if you want to get serious about fostering the ability to concentrate. It’s this mix of transforming your lifestyle to be much more respectful of your time, attention, and cultivate the ability to really take advantage of it, mixed in with the sort of active training activities that then push the limits of your ability to concentrate. You have to do both of those if you’re really going to get to the next level.

Right, and the active training-is that kind of like brain game sort of apps like Lumosity or whatever it’s called or is it something more substantial than that? Is the passive training kind of like just cutting out distractions like putting your phone on silent, going on do-not-disturb mode on your computer when you’re going to work, hiding a bunch of the open windows, or is there a lot more to that?

Well, there’s a lot of different things that fall into these categories, but the type of things you’re mentioning, that’s in the ballpark. To give you a couple of concrete examples for active training, one thing you can do is, actually, interval training. You can take something like the Pomodoro Technique where you’re going to give yourself a fixed amount of time, and during that time you’re going to concentrate intensely on a single task. If you break your concentration at all-even just a quick check of an email inbox or a phone-you have to reset the timer; the Pomodoro doesn’t count. If you start those at a small amount of time, and then after you’re succeeding at a frequent basis with that amount of time, you add 10 minutes, you do that until you’re succeeding with a new amount of time, you add 10 minutes, you can basically replicate similar to interval training that you would do for running times or muscle training.

You can start at 20 minutes at a time if you’re brand new to deep work, and over a period of six months, you might end up at a place where you can then very comfortably go 90 minutes to 2 hours without needing distraction. That is sort of a concrete example of active training. On the passive side, I’m pretty extreme in what I recommend. For example, this idea that you should occasionally take breaks from distraction-maybe you should have like an “Internet Sabbath” every week, which I think is nonsense. I think that’s like saying you’re going to get healthy or you’re going to lose weight by taking one day a week where you eat healthy. It’s not going to work if the other six days you’re getting junk foods. I actually recommend that your mindset has to flip. You don’t set aside occasional breaks from distracting behavior.

You, instead, take occasional breaks from a non-distracted life to indulge in those type of distractions-maybe, “Okay, I’m going to put aside this hour tonight where I’ll go on my tablet and go nuts,” or “I’ll put aside a couple of hours Saturday morning when I can do web-surfing or do my social media,” but that the default state in your life is one where you do not try to resolve boredom in the moment by turning toward some sort of algorithmically tuned, attention-engineered source of lightweight entertainment. Just like if you want to be a professional athlete, you have to get really serious about your diet, I think that if you want to be a serious deep thinker, you have to get very serious about your cognitive diet-what you allow into your attention landscape.

Yeah, but so many people are hooked on reading the newspaper every day or scrolling through their Facebook when they’re online because what else are they going to be doing while they’re waiting for the checkout?

Well, be bored. In fact, I have a whole chapter in the book called Embrace Boredom. It’s not just about a sort of curmudgeonly white-knuckling like, “Hey, I’m just sort of pushing back against what I don’t like in society,” it actually has a real cognitive foundation. Deep work, by definition, is born if we use the technical definition of boredom-meaning, a lack of novel stimuli. With deep work, you’re actually keeping your attention on a single thing for a long period of time so by definition, there’s not going to be a lot of novel stimuli so it will be boring. Your mind has to be okay with that. If you, instead, culture your mind to expect at the slightest hint of its boredom, you will get a quick shiny treat, which is the term that the technologist, Jaron Lanier, coined for talking about how social media apps, for example, are engineered to give you the shining treats that keep your attention to them.

If your mind is used to that, it’s, basically, biochemically equivalent to an addiction so when it comes time to do deep work, even if you do hike to the top of the mountain, and if you do leave your phone at home, even if there is no WiFi on top of the mountain, you’re still going to struggle to do it because your mind has been trained, “I’m bored, where’s my stimuli?” You do have to embrace boredom throughout your life if you’re going to expect to be able to succeed and persist with the boredom that surrounds true deep work. I think standing in line being bored is a good thing. That is actually going to be the behavior that, down the line, is going to likely produce sort of deeply satisfying, meaningful, and highly-valuable results.

Inside of our brains, the way the chemistry is going-like, if we get addicted to the quick shiny treats, we’re getting all these dopamine hits just by scrolling through our Facebook newsfeed versus a more meaningful kind of serotonin-based treat like we’ve accomplished something really valuable and important for society then that’s way better, and we’re, basically, subsisting on Twinkies instead of a really sustaining and filling meal.

Yeah, and we can’t separate anymore what happens outside of the context of work, and what happens when you’re trying to do work when it comes to the life of the mind. There’s really just a growing amount of research that emphasizes this point from several different angles. How you treat your time and attention outside of work really does affect what you’re able to do when it comes time to really concentrate. They’re not two separate things so just like you can’t say, as an athlete, “Hey, when I’m actually, literally, training, I’ll eat healthy food during the training and drink just water, but at night, when I get home from training, I can eat Twinkies and smoke,”-you can’t do it. Your diet is going to matter. It’s going to affect your training the next day. It’s the same thing with the life of the mind. You’re not going to be able to sit down and produce something that’s cognitively demanding at [9:00] A.M Monday morning if spend all Sunday eating cognitive junk food.

How you treat your time and attention outside of work really does affect what you’re able to do when it comes time to really concentrate.

Right. Plus, you need to be congruent with your view of yourself-your identity.

Yeah.

Your identity as somebody who eats Twinkies when they’re allowed to cheat-that just doesn’t work and that creates an “out.” It’s like saying the word “try” in a sentence-you’ve given your brain an out for not doing the thing that you just semi-committed to.

Yeah.

There’s no commitment there.

That’s such an important point. This is a big reason why I suggest that many more people should quit social media. Now, my exceptions for this are people where social media is directly related to success in their job so if you run a media company like you do where you actually have a media property then okay, maybe it makes sense-you need to be on social media to promote it. However, unless it’s directly related to what you do for a living, I recommend that you quit it. In fact, I just did a TEDx Talk with the title, Quit Social Media. A big reason why I make that suggestion is, not that like, “Okay, even the slightest glance at Facebook is going to ruin your ability to do deep work-although it is pretty addictive so you have to be careful,” it’s more about the self-image that it helps create.

If you say, “I’m not on social media,” that’s like saying, in a fitness context, “Hey, I’m a vegan now or something.” It’s telling yourself, “I am someone who really values my time and attention. I’m someone who seriously takes my ability to concentrate,” so even if you are a very light user of these services, they weren’t really having a major sort of chemical effect on your mind, there are still, as you just pointed out, this very positive self-image-based psychological benefit that you get by taking pretty drastic steps that indicate to yourself, “I’m not like everyone else. I’m someone who really takes my mind seriously and my ability to concentrate seriously.”

Yeah, I love that. I recently-like, last year-gave up sugar, which is a huge deal for me. I was addicted my whole life to sugar. I can’t remember a time that I didn’t devour candy bars and stuff. It’s been since July. I haven’t had a dessert since then, except on my birthday, Christmas, and a couple holidays so that’s just part of my identity now-I don’t eat sugar. I mean, I’m probably getting added sugar in ketchup and stuff that I’m eating, but I just don’t eat dessert, that’s part of who I am, and if you’re somebody who, for example, doesn’t have Facebook installed on their phone, that’s going to free your brain up to be more creative and to be able to work deeper.

Yeah, because you get the double benefit. I mean, first of all, you get the benefit of avoiding the addictive properties, which we have to recognize that a lot of these services are not fundamental technologies-they’re just entertainment services, and they’re a little bit unsavory when you look a little bit deeper. If you look a little bit deeper, it turns out that the most major social media companies hire people called “attention engineers” who borrow principles from Las Vegas casino gambling, among other places, to engineer these applications to be addictive. Their desired used case-the used case that they’re designed for-is one in which they used constantly throughout your waking hours. If you’re not using Facebook or Twitter constantly for your waking hours, you have not yet evolved to the used case that Facebook and Twitter would like you to do. That’s dangerous, right?

Most major social media companies hire people called “attention engineers” who borrow principles from Las Vegas casino gambling to engineer these applications to be addictive.

I mean, it’s fun to go to Las Vegas and pull the slot machine handle for an hour, but to take a slot machine with you throughout the whole day? Unless we got through your whole day, and at night, and in bed, and when you wait in line, and the console would be pulling this, and hoping-that would be crazy, and that’s sort of what’s happening with these applications. There’s almost an unsavory character to it, which is, it’s not just that by happenstance, they’re somewhat addictive-they’re designed to be addictive. You’re, basically, going to a cognitive “war” against these really good attention engineers who know what they’re doing once you let these things into your life. You keep that in mind that it gives you another stronger motivation to leave them behind beyond just the more general point-just like, there are probably some benefits to sugar, but you get a much more powerful benefit by saying, “I’m someone who just doesn’t eat it,” it’s the same thing with social media. I know that you have six stories that you can say of things-well, this happened once when social media was good and maybe this could happen on this side on this, but they call be swamped by the bigger positive benefit to yourself in your work life and satisfaction by saying, “I’m just someone who doesn’t use that. That’s not what I take seriously.”

Right, and it’s not enough to just suppress your urges to check the social platforms throughout the day and still have it installed because you’re going to get hammered with these notifications throughout the day that just interrupt your focus, and take you off into some useless place, and when you were maybe about to come up with this great big idea to change the world. I’m wondering if-let’s say that you are in the business-I’m in the business where I have to be on social media, right? I’m promoting my podcast episodes. I am communicating with prospects-I do SEO consulting and online marketing consulting-so I kind of have to know this world really intimately. I wrote a book about it-Social eCommerce-so I can’t exactly go on a starvation diet of no social media. I do have a team of people who are doing a lot of the social media for me so I’m not the one on there all the time posting, but I kind of have to be on here, and I tried removing Facebook from my phone, and I had to keep reinstalling it, especially now that we have Facebook Live, because it has to be done from your phone. If you don’t do Facebook Live or if you’re doing pre-recorded videos, you get half of the reach. I could install it, but then, half-day later, I have to reinstall it so that I can do a Facebook Live video. What do you recommend in that kind of scenario?

Well, the psychology research that I think is most relevant to the scenario is, the growing body of literature built around the idea that our brains are prediction machines. If you get into a particular routine-this is when I check social media: Every 10 minutes, I look at my phone or every hour, I look at my phone-whatever the routine is, that’s going to cement in your mind, and then it’s just going to run with it so even if you really want to white-knuckle on a particular day and say, “I’m just not going to be distracted for three hours,” your mind doesn’t care about that. It’s much more interested in actually following its learned rhythms and routines, and it will interrupt you, and crave social media at those trained intervals.

For someone who has to use it professionally, the key thing is to set routines that are going to be as non-disruptive as possible because whatever routine you set and your brain locks into, you’re going to be locked into that, and it’s going to be very hard to maintain concentration beyond what you actually are used to doing like when it comes to when you check it. My recommendation for people who need to use social media professionally is for you to have incredibly clear routines and systems for when you check it, and what you do with it when you check it. With those routines, make sure that they’re very sparse so that your mind has a sense of “It’s the beginning the day” and “It’s the end of the day” so there are huge gaps in which it’s not expecting to see social media and that you don’t check it casually outside of work.

You don’t allow your mind to get set into a routine that you’re going to see this frequently, and that you use tools like Freedom to walk in these routines as hard as possible at first-that you’re really sort of forcing yourself, “I literally can’t see it until this next check-in, and at the end of the day, it’s locked down. I can’t check it until morning,” because what you really want to avoid is your mind getting locked into the schedule of, “I’m going to see these stimulants at a relatively regular basis,” because once it’s locked in, it’s going to be really hard to white-knuckle pass those schedule checks. It will interrupt whatever you’re thinking about and crave it so have a good answer for the question-here is how I do social media and how I enforce it.

Right, and speaking of the cravings, one thing I’ve found with sugar-actually, with Netflix too-I cut out Netflix pretty recently like, within the last six months, and no more Netflix. We don’t have cable and we don’t have Netflix. We have a television that’s not hooked up to anything except a DVD player so yeah, there were some cravings. It was tough at the beginning, but you get used to it, especially if you done that identity shift, and you’re not just the person who wastes a bunch of time on Netflix. I’m a big fan of scheduling your entertainment-you don’t just sit and veg out in front of the TV because you’re tired, and you’ve had a long day.

You schedule your entertainment. Netflix and chill-you just don’t do it, and that’s probably going against almost every one of our listeners-that’s going to be heresy for them-and yet, if you think about-let’s come back to the idea of suppressing the urges, and cravings versus something in Kabbalistic learnings from Kabbalah that’s called “restriction” where you are restricting something that’s a short-term pleasure, but a long-term pain or something that’s negative, whether it’s smoking, or vegging out in front of Netflix, or eating a big bunch of candy, or checking social media incessantly instead of getting actual work done. With restriction, you gain power and you gain energy. It’s feels empowering and it feels good to restrict versus suppression that feels uncomfortable and painful. It’s cravings-it’s kind of like suffering.

Yeah.

I was suppressing my cravings for sugar, and then I hit a point where it flipped, and I started restricting. It was a point where I was in a sugar challenge with my youngest daughter and my fiancée, and we were all doing a sugar challenge for two weeks, but I wasn’t the leader-my fiancée was-and I was cheating and stuff. We finished the two weeks, and she’s like, “I’m out. I’m done. You, guys, do whatever you want, but I don’t need this. I can take care of myself,” and she did, but then I went to my daughter and said, “Do you want to do another week? I will if you want to,” and then I became the leader because she said yes, and then it started becoming restriction, and then I changed my identity around “I’m not a person who eat sugar and pollutes my body.” It was downhill from there-it’s just really easy. I think it’s important for our listeners to understand this distinction that you don’t have to be in this painful place of suppression of urges, you can have this identity shift, and then you’re restricting, and it feels good, it feels empowering to know you’re feeding your mind and your body in an empowering and wonderful way.

Right. In fact, I quote in the book Arnold Bennett talking about this notion of scheduling your leisure time, for example, and giving yourself well-cultivated activities that are going to better you as opposed to the early 20th century or late 19th-century version of vegging-not when he wrote that, and he addresses the argument that people have. He says people, even back then, would argue, “No, no, no. I can’t do these sort of intense, planned leisure activities in my time after work because I’ll be exhausted. I need to just that veg to regain my energy,” and he says-and I’m paraphrasing-“That’s nonsense! Actually putting your mind to work on something of value is going to leave you feeling more energized than if you just try to shut down your mind to do nothing until the next day.” It’s not a heresy to me. I’m a big believer in this notion that there really need be no place for this sort of algorithmic, lead-generated, lightweight engineer to be an addictive-type of online content in your life.

Yeah.

Putting your mind to work on something of value is going to leave you feeling more energized than if you just try to shut down your mind to do nothing until the next day.

You don’t need it. In fact, you will be happier, more relaxed, and more energized. You’ll feel better about yourself and your life if you just say, “That’s not me!” If a headline has three commas in it, and starts with the word, “Yes, actually, blah-blah-blah…” I’m not going to read it. I don’t look at a Facebook wall, and I don’t really care about weird Twitter-that’s not me. As you say, it’s a huge shift, and it doesn’t feel like suppression after a while-it becomes a real source of energy and pride.

Yeah, and also, you’re not susceptible to the filter bubble, which is really important for people to grasp that they are getting spoon-fed their news through social media in a way that is highly-engineered, and it keeps them in this bubble not knowing what’s really happening outside, but just what is going to get the highest engagement metrics for you. Also, it’s very skewed in its outlook of so you might feel, “Wow, the news is all about X,” right? It’s all about some particular issue that happened somewhere in the world, but it’s because you have shown engagement metrics-you’re engaging with that content, and so it’s going to feed you a lot more of it, and then we just get very skewed in our outlook of life.

Yeah, I agree with that.

Yeah, so what are your favorite tools then to kind of keep this in check? You mentioned a tool called Freedom. Do you also use Rescue Time or Way of Life? I mean, what are some of the things that help with kind of staying on the straight and narrow?

Right. Well, especially when you’re doing the training-so you’re, first, leaving a sort of more distracted life for a deep life. Two things that are useful are: (1) start scheduling your time. I’m not a big believer in to-do lists as a planning tool. To me, a to-do list is not planning tool, it’s just a repository of information that is useful when you actually try to plan your time. To run your day off a to-do list is something that I think is highly inefficient. Instead, I suggest that you actually time-block your day-what are my hours of the day and what am I doing in the different hours? Give your hours a job so you actually have to confront how much time you actually have, and you put in the media and disappointment and while I’m commuting, you see what’s actually there, and you start saying, “Well, what could I actually do in this hour that’s free here? I have three hours here that I will actually want to put in there,” so that you become more active and responsible for the time in your day, as opposed to being just sort of more reactive, “Okay, what do I want to do next? What’s on my list?”

Then, I do recommend tools like Freedom to help, at first, enforce these decisions you make against about your time so if you spend two hours working on writing this thing, then you can just click this button that cuts you off from all of the sources of destruction, including, crucially, email for those two hours. If you have an hour of task and to-do’s, then you have access to all that. And then you have, maybe, a three-hour thing after that, shut it all off. After a while, I mean, if you get social media out of your life, if you train yourself like you’re talking about to not use the internet for entertainment, if you sort of detox yourself from a lot of these sorts of distraction, you don’t really need a lot of tools to enforce this absence anymore-it just becomes natural and just part of your identity. I think these tools are a great sort of detox program, and then the thing you use going forward, in my mind, is you become much more willful and specific about how you’re going to spend your time-you plan your day, you plan your weeks, you would move your obligations around like chess pieces so that you’re always making active decisions about, “What am I going to do with my time?” and you always have to justify it yourself, “Why is this the best use of my time?”

Right. There’s this idea of having a device dedicated to a particular type of work-for example, entertainment is only going to happen on your iPad so if you want to watch a movie on Netflix, you’re going to have to go on your iPad for that. It’s not even an option on your laptop. Maybe you’ll have two laptops, and the one you write on is your older one that you have uninstalled email, web browsing, and everything else, and all you do is you write on that. What’s your position on kind of having different devices dedicated to different types of activities? Or, even having different areas of your office or home dedicated to certain types of activities-like, never working on “work-work” in the bedroom, or never having TV in the bedroom because that’s only for sleeping and for the other thing-what’s your position on that?

Well, the latter point is an important one. It’s a habit that comes up often if you study people who are adept at deep working, which is that, they’ll have certain locations that they associate just with deep work. It could be a different office, it could be a particular chair, it could be a completely different building, or it could be like Charles Darwin’s sand walk-an actual path that you walk on when you do certain types of deep work. That’s useful because it helps your mind transition into a deep work mindset. There’s a habit around it in a way that expands much less energy than if you just try to, in an ad hoc matter, rinse your attention away from interesting things and force it to concentrate so having deep work locations is something I really recommend.

I know some people who don’t have a separate location, but do a physical transformation of their work environment to make it conducive to deep work and to signal that change-they’ll clean the desk, change the lighting, turn off all the lights except the desk light, put a “Do Not Disturb” sign, and close the door-just that transformation of what their work environment looks like is enough to trigger in their brain the same sort of habit of, “Okay, now we’re shifting into the deep work mode.” In terms of separate devices, again, I think when you’re going through the transition into a sort of deeper lifestyle, using tools like Freedom that help restrict access to things you don’t want to, or having a separate device that’s not connected to the internet when you do a particular type of deep work, all this helps that training, but in my experience, once the deep life has become a part of your identity, It’s just not so important because most of these things just don’t have a big footprint in your life anyway.

Locations are something I’ve seen adept deep workers used to great advantage.

If you’re not on social media, if you just don’t have a habit of web surfing-for example, I don’t web search so I don’t even know what web pages I would go to for entertainment. I just don’t have a cycle of my pages. These things don’t really matter so much anymore so hopefully, that you just detox from enough that it doesn’t really matter, right? I mean, I don’t really have a lot of things on my device to distract anyway, but the locations are something I’ve seen adept deep workers used to great advantage.

Yeah, and one person you mentioned in particular in the book really struck me-Carl Jung and how he had a completely separate location for his deep work, which was out in nature. He would be there-hole himself up for days at a time-and just really focus. He didn’t take patients or anything in there. He would have completely separate worlds.

Yeah, it was a house he built in the countryside outside of Zurich. People still use that technique today. I talked about, for example, the professor and author, Adam Grant, who’s a professor-a business professor-at Wharton and bestselling author. He does Carl Jung strategy, except that he doesn’t go to a cabin in the woods, but he does more or less the same thing-he disappears for multiple days at a time, and puts an “out of office” responder in his email, and he treats those periods like he’s overseas. “I am gone for these days. I can’t be reached. I’ll be back on this day.” He does the same thing when he’s going to do deep work-he drops off the radar, he is completely unreachable, and he does the deep work. I call that the bimodal philosophy to scheduling deep work, and it’s a really effective one if you have the type of autonomy in your professional life that allows you to get away with it.

Yeah, that’s the thing. I have a lot of freedom and I could pull that off, but I haven’t yet. I might-I just might. One thing that is kind of similar to this idea of separate locations. I heard about this several years ago from Keith Cunningham. He espouses this idea of having a thinking chair where you only sit in that chair when you are going to do really deep thinking about your strategy, your business, your life-like, what are your 10, 20-year goals and things like that-and other times, you just never sit in that chair. I don’t know how often he sits in his thinking chair, but he has the thinking chair that he only sits on when he’s going to think. He doesn’t bring his laptop, and it’s just notebook and pen.

Yeah. I have a thinking chair. I spent a lot of money on it just so that I would take it seriously. I’ve blogged some about it. It’s a big, nice, leather chair in the corner by a window, and I read in it, and I write it.

Very cool! How often do you sit on that?

I’ll say, half the days of the week, at least. If I’m going to read something hard or write something hard, I like to go to it so pretty frequently.

Wow, that’s amazing! Do you schedule the time where you’re going to be in that thinking chair?

The ability to structure my time allows me to have large periods of time set aside and protected just for creative thought.

Yeah. I’m a big proponent of scheduling your time, and I get pushed back on this. People, I think, are legitimately worried that if their time is scheduled, that it will, somehow, be too rigid, and that will suppress creativity. They’re also worried that their schedule changes, and so if you schedule your time, your schedule could change. Neither of those things, I think, however, are reasons not to do it. First of all, there’s not a lot of evidence that people of true creativity really draw from free-form schedules. That, somehow, rigidity and schedule is going to prevent creativity. The ability to actually structure my time allows me, for example, to have large periods of time set aside and protected just for creative thought. I spent two-and-half hours this morning on foot just thinking about a problem. That’s the type of thing I can do because I control my time.

If I, instead, just said, “What’s in my inbox? What should I work on?” I probably would not have had that much time uninterrupted just to think creatively so I don’t think that structuring your time, somehow, suppresses creativity. To the notion that your schedule might change, my response is, great, then just change your schedule. It’s not that big of a deal. You made a schedule for your day, it changes at some point, so make a new schedule for the rest of the day. If you have to do it three times, that’s five minutes you’ve spent, and, still, all the other time in the day, you’ve gained the benefits of being more intentional about your time. I’m rigid. My hours of the day are scheduled. I have a plan for my week. I have a plan for the quarter at a higher level of granularity.

I just find that you can squeeze much more high-value production out of your life if you actually have a high degree of control of how you spend your time. In other words, the less control you expand on how you spend your time, the less high-value output you can produce because high-value output is really dependent on sort of long periods of deep work that are set aside and protected, and that really just requires a lot of control of your schedule. It’s not the type of thing that you’re just going to stumble upon in your normal schedule, and just happen into long periods of time where you feel like you’re in the mood to concentrate.

And how long should these periods of time be? Do they to be like, five hours before you can really get in the zone? Let’s say, you’re writing a book-is two hours a long enough chunk?

Well, at least 90 minutes is what you want to do without a real distraction because it takes 20-30 minutes just to clear out the attention residue from whatever you were doing before that blocks. If you only work for 45 minutes, you only really get 10-15 good minutes in there at a high cognitive capacity. Now, during these longer blocks, you might concentrate for a shorter Pomodoro, and then sort of back off for a little bit, and then attack again, and then back off a little bit, and then attack. That, you can train so those periods of unbroken concentration get harder, but in terms of a block of time in which you really don’t let unrelated distractions into your life, you really want to start with 90 minutes, if possible, as a base amount, and those can get much larger, right? I mean, it’s not surprising for me to have a day or two in my schedule, or I might do six, seven hours where there’s no distraction let into my life-there’s no email, there’s no checking of the phone, and it’s really just working in dashes on the same problem the whole day. You can get there with some training, and then those days become incredibly productive.

You can squeeze much more high-value production out of your life if you actually have a high degree of control of how you spend your time. Share on XRight. You mentioned attention residue-that is a really important concept. I got a lot of value out of that, and in the book. Essentially, what happens is that your brain is still preoccupied with the previous activity so it bleeds over and affects your ability to perform at a high level on the activity that you’re currently working on. This idea of multitasking or of doing a lot of task-switching just destroys your productivity because of the attention residue, and there’s science behind this too. Could you elaborate?

It’s a really important point so yeah, as you mentioned, the basic concept of potential residue is, if you switch your attention from one target to another, there’s a residue left from the original target that can last 10, 20, and even up to 30 minutes, and while that attention residue is present, your cognitive capacity is reduced-you’re just operating slower from a mental perspective. The reason why this is very important is that we made the shift as a sort of work culture. Somewhere in the early 2000s, we made the shift away from pure multitasking. In the late ’90s and early 2000s, people used to brag about peer-multitasking-you know, where you would, literally, have an inbox open, and you’d be looking at that while writing something while talking on the phone, and people have bragged, “I can do all these things at the same time.”

A lot of research came out led by the late Clifford Nass of Stanford, among others, saying that you can’t multitask. If you’re doing multiple things simultaneously, you’re really just switching rapidly between them, and you pay a cost for the switches, you’re doing them all worse. Okay, so as we get to the sort of the second decade of this century, people no longer brag about that, right? I mean, people know now that you don’t leave an inbox open at the same time they are working on something else. You don’t try to talk and write at the same time. But what people are doing instead, is what I call the just checks. They think they’re working on just one thing for a long period of time, but every 5 or 10 minutes, they do this really quick “just check” of an inbox, or a really quick “just check” of the phone, and it’s these brief checks, right? They’re not multitasking. They’re doing one thing, but they, of course, just have to kind of check these things.

However, we know from attention residue theory that it’s just as bad because even a quick glance at an inbox-if that shows you an email in there that you know you’re going to have to answer later, and it’s going to take well the answer, you’ve just killed your cognitive capacity for the next 20 minutes. Most knowledge workers are doing these “just checks” at least every 5-10 minutes, which means that most knowledge workers are working in a persistent state of reduced cognitive capacity. It’s like, as a work culture, we’re all collectively decided to take some sort of anti-neurotrophic-some sort of drug that just makes us worse at concentrating, worse at doing work, and makes us worse at our job-and most people don’t even realize that this is going on because they say, “I am not multitasking. I just glance for 30 seconds in my inbox. That’s not multitasking,” but it has the same negative impact. It’s part of why deep work is so effective because it requires you to go a long period of time with no distraction, no “just checks,” and no changes of your attention target. You actually get to get to a state of no attention residue and work at the full capacity of your mind so in comparison to everyone else, it gives you this real cognitive advantage.

Right. I heard the terminology well before I started learning about your book called, urgency addiction, and then I’m like, “Oh yeah, I’m hooked on that!” I used to check email first thing in the morning. I check email constantly so now, I avoid that. I go through a morning ritual-I meditate, pray, and get into the zone-before I start digging into my day. It’s way more intentional, and it’s way more powerful. You get a lot more cognitive cycles that way, and you feel way more accomplished by the end of the day. It’s hard for somebody to establish a whole new routine for their mornings where they’re not even checking, and they’re like, “I’d lose my job,” “I can’t just not be available first thing in the morning,” “Things have blown up overnight!” “There are things going on in other offices!” or “We’ve got developers in India, and they’ve been working all night. I need to see what they’re up to as soon as they wake up!”

Yeah.

What do you tell them?

Email is having an incredibly negative effect on the productivity of the knowledge sector in our economy.

Email is incredibly addictive, and I think it’s having an incredibly negative effect on the productivity of the knowledge sector in our economy. This works well, but that we have developed surrounding email where work is basically dependent on this ongoing ad hoc conversation that happens over Slack and email channels. This style of work is at exact odds with the proper optimal function of our brains. It makes us terrible at actually doing the knowledge for which we are highly-trained to do, and for which our brains have been trained to do. It’s sort of a disastrously unproductive approach to our work, and it’s something that should be really scary.

In other words, if you say, “I spend most of my time doing email. I can’t be away from my email,” you have to recognize what that means is, you’re basically acting as a human network route-that you are spending most of your time shuffling information around, which is an incredibly low-value activity. It’s something that I can tell you as a computer scientist that we’re getting better and better at automating. It means that are doing something that within five years, we can have computers do instead. That means, you’re not spending your time actually doing the type of creative deep thinking that actually differentiates humans from the type of activities that can be automated, eliminated, or outsourced. If you say, “I have to be on email,” your next thought should be, “And that’s a huge problem so I either need to change my job or how I do my job.” How do you that?

One strategy I suggest, is actually having a conversation with whoever’s above you where you explain what the concept of deep work is. You explain that there’s deep work and there’s non-deep work-both are important, and we need both for the business to function. What should my ratio of the non-deep work hours be in the typical week? And have this conversation, and actually have the boss nail this down and think about it. “Okay, what fraction of your time do I actually want you using your brain and try to produce high value stuff, and what fraction do I want you doing this necessary, logistical coordination activities?” Once you pin down this number, measure and discuss, and come back and say, “Hey, we’re falling well short. Why am I falling well short? What’s happening to our work culture?” You’d be surprised by how much flexibility there actually is in a lot of work cultures.

I told the story recently on my blog of a marketer from Silicon Valley who was really feeling slammed by communication. His company had this culture that if you didn’t respond to a Slack comment almost immediately, the assumption was you’re slacking off-that you weren’t doing your job and that you weren’t available. This was the culture. He had read what I suggested about the deep-to-shallow work ratio conversations so he went to his boss and said, “What should my ratio be?” and he said that as soon as he brought it up, it was clear in the room that it would have been ridiculous for her to answer, “I want you to be doing mainly shallow work,” because this is someone who is being paid a lot of money, primarily, to do something that was very deep. He had to write these very complicated articles that they use to help market the product. They decided it should be about 50-50-it made the most sense so then they thought about it, “Well, how am I going to get this 50-50 ratio?” and they said, “Oh, well, why don’t we just set up a schedule where you have these two hours in the morning, the two hours in the afternoon, and those are deep work hours, and we’ll tell all your colleagues,” and they had a meeting about it and said, “You can’t contact Tom during those hours.”

He said it took about a week to get used to it and now, they don’t care. It’s fine. They know that, “Okay, I can’t contact Tom during those hours,” and he was getting four out of eight hours a day uninterrupted and doing deep work. You’d be surprised how much the seemingly unchangeable work cultures can change overnight once you actually open up the lines of communication, and start using terminology like deep work or shallow work, and having honest conversations about what roles should each of these play in my work day.

Yeah. In fact, you mentioned Slack, and I recently read an article that was really slamming Slack as a productivity killer because it does not save you time by taking stuff out of your email inbox, but instead, it causes all these banter back and forth of unnecessary noise that we become trapped in this ecosystem of back and forth, back and forth, and it just sucks all of our productivity.

Tools and technology have the capability of changing completely what we mean by work.

Yeah, and I think this is important to emphasize, and this is a new thought I’ve been working on-I’m actually working on a project on this right now. When it comes the tools like email or Slack-sure, it’s not the technology itself that’s intrinsically bad. There’s nothing particularly good or bad about a set of network protocols, which is all that email is, but what has to be recognized is that, these are neutral tools in the sense that people like to think, “I have my work, and then I sort of use tools like email or Slack when it seem like it might may be efficient or make my work a little bit better,” that’s not actually how these type of tools affect people. I mean, we know from a centuries worth of history of technology and media criticism that tools have the capability of changing completely what we mean by work.

They can completely transform what we even think work means, and what’s important is that, these transformations are undirected. No one ever sat down and said this would be better. No committee ever got together or business experts to say, “This is how we’re now going to work-now that these tools are here.” They just have the ability, by their mere presence, to, in the merchant fashion, radically transform how we think about our day and how we think about work. I think this is what happened when email and related tools came onto the scene. Very subtly, but also very persistently, it transformed the way we approach work in the knowledge sector towards a style of work that I call the hyperactive hive mind, which is based on this notion that you want very low logistical overhead. You don’t want to have a lot of processes systems or rules.

You don’t want to have a lot of structure to what you do during a given day. Instead, everyone just has an email address associated with their name and a single inbox, and you just figure out everything flexibly on the fly by ongoing constant conversation. There’s no need for systems tools or overhead, we’ll just keep this ongoing conversation happening-“Hey, there’s a new client, maybe, they’ll start talking to other people in the company, can you look at this? What about this?”-new projects unfold in the sort of ad hoc flurry of messages. This is a very specific approach to work. It’s a work philosophy that’s very specific, and it’s one of many different ways that we could approach work. Once you recognize that, you recognize that it’s not synonymous with work in a digital age, it just happens to be the default approach that people happen to be taking in so I’m a big advocate that we’re going to see a major transformation, and that the first individuals and organizations to get away from this hyperactive hive mind, where we just, “Let’s just figure everything out in conversation all day long,” and move towards other more structured, less convenient, but incredibly more productive and satisfying approaches to work, these organizations are going to really thrive in this ventricle of an economy.

This is my prediction: Fifteen years from now, you’re not going to see workers sitting there with a single inbox associated with their name just sort of checking messages all day. We’re going to look back at that 15-20 years from now and say, “Isn’t that funny? How we did them in the first age of sort of digital networks? Isn’t that funny how we started the work? How stupid and how unproductive it was?” and it’s going to be a curiosity. That’s my prediction.

Yup, I agree. I mean, the open-plan office environments that startups are so keen on because you could just, within a few feet, start chatting with your co-worker-it’s just ridiculous. It’s a productivity killer. Even if everybody’s in separate offices and the doors are open, people will just get acclimated or accustomed to this idea of, “Got a minute?” meetings.

Yeah.

Like, “Hey, got a minute?” and they just completely destroy your productivity, and I’ve heard that it takes seven minutes-once you’re distracted by somebody’s interruption, it takes seven minutes to get back into the zone, minimum, before you-

Minimum, yeah.

-get back into where you were at before the distraction.

Once you’re distracted by somebody’s interruption, it takes seven minutes to get back into the zone.

Yeah, it doesn’t make sense to me. I think the right analogy here is the industrial revolution. I’ve been doing this research recently, but if you go back and study the history of the Industrial Revolution, you’ll see there was a very long period when we’re still trying to figure out how do we run a factory in the industrial age-how do we run one of these big companies? At first, the techniques like the putting out system and the subcontracting systems were very inefficient, but they were convenient, right? It was just easier for the companies to just use these systems-we use subcontracting and we used the putting out system-and then at some point, the decision was made that convenience is not enough.

We actually have to ask, “What’s the right way to run these organizations?” that’s actually going to produce the much value, and that’s how we got things like the assembly line, which were incredibly less convenient than the way they were doing it; incredibly more complicated-there was plenty of hard edges and exceptions that came up-and it was much harder thing to organize and run than the old convenient ways, but it was like a factor of 10 more productivity. I mean, you could put out a factor of 10-100 more cars per day using these systems. That’s what I think is going to happen in knowledge work. It’s just very convenient if everyone is just attached to an email address or Slack handle, and you can reach everyone at all times during the day. It’s very convenient, but convenience is not the goal.

I think the first companies to figure out the cognitive equivalent of the assembly line, which can be a pain, it’s going to be really inconvenient, and you’re going to be in situations where you say, “Oh, crap! I really need to reach Stephan. I need something from, and I can’t, and I’m stuck for a while!” You’re going to have those type of situations and yet, you’re going to have to eat it because it means people are ten times more productive. The first companies to figure that are going to thrive-just like we went from these simple factories that were convenient to these incredibly productive inconvenient factors like the assembly line, it’s got to happen with communication technologies. We can’t be prioritizing-if you talk to anyone about email or Slack, what you get back are these particular exceptions, but what if this happened? Or, what about this time last week when something came in, and I was able to reach out to someone that we could turn on really quickly? It’s a culture of convenience above productivity, and I think there’s no way that’s going to persist.

Yup, and if you do persist with that or insist on not changing, you will become obsolete, you will become like the Uber driver who it’s just a matter of time before he or she is replaced by robots. By the autonomous, auto-driving cars. I remember this one Despair.com poster-these de-motivational posters-that are all really hilarious. This one is on motivation: “If a pretty poster and a cute saying are all it takes to motivate you, you probably have a very easy job iRobots will be doing soon.”

Well, I think you can amend that and say, “If you spend 90% of your cognitive energy today communicating with other people, you’re doing like, an incredibly basic computer task, and we’re getting really good at automating it.” It’s the same thing.

Exactly!

I just did this speaking event with the CEO of this company that’s just going out of beta this summer. They spent three years and $30 million dollars training an AI to schedule meetings for you via email, and it’s fantastic at it. In fact, most of the people who are using it, don’t realize they’re talking to an AI. It just handles that for you-you CC this address that’s connected to this AI, and you say, “Hey, I want to set up a meeting with Stephan sometime next week, probably like a Tuesday or Thursday, but not in the afternoon,” and it just takes over, and we’ll start having a conversation with you, and figure out a time that works. All right, if we can do that now, we’re like four or five years away from doing basically everything you’re doing when you’re in your inbox and sending messages. If you don’t have a good answer to the question, “This is what I do when I’m not sending emails that is really valuable and hard to replicate,” you’re going to be in trouble pretty soon.

Yeah. In fact, I avoid spending any time in my inbox. I never use my inbox as a way to manage my activities. I have a to-do list. I use things on the Mac on my iPhone, but even that, I’m not using. As you described it, it’s not how I planned out my day. I schedule my day out, and I figure out my three absolutes for the day, independent of the to-do list. I mean, I used the to-do list as input and as a resource to help me decide on my three absolutes for the day, but then I schedule that in, and I make sure to get those three absolutes done. If you’re trying to manage your life based on your inbox, you’re doing it completely wrong. One question I had for you when we were talking about scheduling your day is, do you also theme your days? I know Mike Vardy does this-who I recently had on this podcast. Mike Vardy runs the Productivityist podcast and blog-for listeners who haven’t heard the episode, it’s definitely a must-listen-but he talked about how he changed to theming his days like having an AV day, having an interview day, a podcast interview day, and so forth, and it just really took things up a level. Is that how you operate or do you have a different approach?

There’s great productivity advantages to not trying to do a little bit of everything every day. Instead, letting days become much more homogenous.

I do something similar. Not as formal as Mike’s system, but something similar because I’m a believer in having less diversity in a day. In other words, if you have various things you need to do in a typical week, don’t try to do a little bit of each every day. I’m much more a believer of, “Okay, I’m really getting into this thing today, and this is my day for it,” and then tomorrow, I’m really mainly getting into this thing, and then the next day, I put all my meetings in there, and I’m going to try to catch up on everything-all that to-do’s, tasks, emails, and stuff I missed, I will try to catch up on them that day-and then the next day is all about this thing. I do think there’s great productivity advantages to not trying to do a little bit of everything every day and instead, letting days become much more homogenous.

Okay. Do you have separate-do you use Google Calendar or do you use some other calendaring application where you might have a separate calendar overlay that is related to your blocked-out project time or do you have that all in just one calendar? Because I’ve set up a separate project calendar for blocking out chunks of time to work on big things, and then I change things around if I need to-like, if I have an important prospect call that I need to do, and they only had availability during one of my project blocks so I’ll go in and change my project box. I don’t allow my assistants access to change my project blocks-they just look at it, and modify my main calendar.

Yeah.

That works for me, but I’m curious what you would recommend.

I use Google Calendar. I don’t use a separate overlay for my deep work blocks, but I do absolutely keep those deep work blocks as scheduled appointments on my calendar. What I try to do is, be at least one month out into the future-the farther, the better. In other words, I claim my time for deep work way in advance, and the reason is, if you don’t do this, what I found is that, you begin to nickel a day and dime away time in your days in the future because someone will say, “Hey, can you do this meeting?” and you say, “Yeah, why not? I mean, I’m looking three weeks in the future. That day is completely clear,” and then someone else will go, “Can we do this call?” and you’re like, “Yeah, why not?” and then you do it earlier, and then when you finally get to that week, you realize that every day has a sprinkling of things that makes it impossible for you to have these long, uninterrupted periods that’s necessary for deep work.

I’m a big believer in claiming that time for deep work way out in advance so that as other requests for your time come in, they have to work around these long, uninterrupted blocks of time. It doesn’t greatly reduce the number of things you’re able to accept, it just ensures that they get consolidated in a way that actually supports the big rocks, which is deep work in this case. Now, how you actually choose how much time and when you block off these deep work blocks, there are different schools of thought for that. One school of thought is that, you have some sort of set routine-these days, these times every week that’s deep work time, and in that case, you could just have these as like a repeating event in your calendar.

The other school of thought, which is sort of my school of thought is that, I actually work with the contours of the weeks so each week will look different. In different seasons of the year, I have a general sense of how much deep work I want to be doing, and when that is might be different from week to week. If I’m away and giving a speech on this date, then I’ll offload it more on this date-that type of thing. The other school of thought is I do more like Adam Grant or Carl Jung, and you say, “I’m blocking off this week,” and then no deep work for the two weeks that follow, and then I’m blocking off this long weekend. The common thread through all that though is, deep work is protected like any other media and appointment, and it’s set and protected far enough out into your future that you’re not going to nickel and dime away days so that when you get there you have no freedom.

Claim your time for deep work way in advance.

Yeah. There’s another methodology that’s recommended by Dan Sullivan-strategic coach, Dan Sullivan. He talks about buffer days versus focused days versus free days. If you decide that you’re going to do some administrative stuff, make some phone calls, and things then that’s a buffer day. But if you want to get focused work done and really make headway on some big project then that needs to be a focus day, and no buffer day activities on that day. For free days, you just are off the grid, being with your family, doing your hobbies, or whatever, you’re just not even thinking about work.

Yeah.

What do you think about that approach?

I’m a believer in that general approach as well. I mean, what I found in my own life, and it’s true for a lot of other professions where it’s not just you, for example, in your own company is that, you can come close to that. Often, what ends up happening is that in a deep-thinking day, you’re going to have a block somewhere that does sort of a mad dash of trying to keep the fires from burning down your house-the people from outside your organization, your boss, this and that, that you have, at least, acknowledged that you’ve heard from them, and when they can expect to hear from you. The key is to put that block at the end of those days. Don’t start your day with it. Do the whole thinking day, and then the last thing you do is, you have your hour to spray down the house with a host so the fire doesn’t burn it down, and that seems to work. I’m also a big believer in some sort of habit-as a college professor, I have these simple heuristics.

When I’m teaching, I just make my teaching days my administrative meeting days, and it’s just automatic. If you say, “Hey, can you do a call? Can you do a podcast?” it’s like, yeah, Tuesday or Thursdays, that’s when I can do these things. Because my classes are going to break up the day enough anyway so I’m not going to be thinking days like that, so having simple heuristics like that has also been useful. When I just sort of know in advance that these are the days when I always say I’m free, and that also ensures a good consolidation. I like Sullivan’s system. I find for people in larger organizations that it’s hard to have the full day on a consistent basis with no contact.

Although, I do recommend to a lot of people-and I do this-is that, you just get worse at email to the extent that you’re able to, and just apologize. And you say to the clients, “I know, I just don’t check my inbox that often.” If this is a problem, what type of system can we put in place to make sure that we get around this? Okay, if the issue is, “I need to know that you’re making progress on your work,” and you say, “Well, why don’t we set up a thing? A project management site where I’ll post updates every day to show what has been done,” or I worry about, “What if there’s an emergency?” “Well, let me give you a text message, enter your number. If there’s a real emergency, text me, and I’ll get you a phone as quickly as possible,” and they never will. Or, we’re working out this project. You say, “Well, I think what we need to do is have a longer meeting at the of the week, and take the time to figure out the whole thing as opposed to working on it.” In other words, be bad at email, acknowledge that you’re always going to be bad at email, and when that’s a problem, say, “So, what else can we do to get around that?”

Yeah.

And I found that in my life that’s been useful. I just apologize a lot.

Or, you can just be really good at email, but it’s not actually you, right? So, if you are communicating with me at my St*****@************er.com email address, I’m not seeing that. Typically, it’s my one of my assistants-one of my VA’s. I have a whole episode where I interviewed my former VA who was amazing – Carolyn Ketchum. We talked about all the processes that I had in place, and I still do have. That means, I’m not ball and chain connected to my e-mail. If there’s some sort of fire that needs to be put out-if a client is in an emergency situation-my assistant will text me or call me.

Yeah.

It’s high responsiveness. I don’t have to apologize. I just have to trust that this is my email address that I’ve had for a very long time and everything’s in there. Everything. I mean, I’ve given the keys to the kingdom to my trusted VA’s.

Yeah.

And for a lot of people that’s scary. I mean, some of my VA’s even have my credit card numbers.

Well, what you’re doing, which excites me, and what I think we’re going to see more of is, breaking out of the cultural convention, which dates back to the early days of the internet, into a tech culture that’s not congruent with life today. That there’s this obligation that an email address associated with your name is like an in-person conversation is. It’s an open-channel communication that you have the responsibility of being there and responding, and to not answer an email directly and by yourself would be like someone standing in the room talking to you, and you just turn away to ignore him. We have to be more willing to break this convention so I love what you’re doing.

Two other examples I’ve seen of that are: My friend, Brian Johnson, who also runs a fantastic podcast. What happens now, if you write him to his email address, he says, “I don’t use this anymore, but here’s the address of my assistant so you can send what you need to them if it’s important, and he can always get in touch with me if it’s urgent.” He said that just adding that extra step of indirection killed off 95% of the emails that came in. Nothing about it is saying, “I can’t be reached. I don’t want to hear from you,” it’s just, “Okay, you’re now going to have to talk to someone else, and they’ll bring it to my attention if it’s important.” Ninety percent of the emails that are coming in, people self-filtered and we’re like, “Okay, I didn’t…” because it’s so easy to send out a message, “Okay, maybe I don’t really need that time and attention,” and so he basically-and then he talks to this assistant once a day, and he has been fine.

90% of what was valuable to me had nothing to do with communicating to people through email. Spending more time on my content returns more value than 10-100 conversations I have in email.

The more extreme example, which I also love, is I wrote this article about how two web entrepreneurs so Pat Flynn, who runs Passive Income podcast, which is an incredibly successful website and podcast, and Brett McKay, who runs a very successful Art of Manliness website and podcast. They are both suffering from email overload and so Pat Flynn, he went beyond even the virtual assistant route and hired an actual executive assistant so someone who’s highly-trained to work with high-level executives to full-time work on his email inboxes, and it helped reduce the load. What Brett did, which I think is great, is he just said, “I don’t longer have an email address on my website.” He just got rid of it so, “Here’s a mailing address if you really need to reach me.” It turned out actually 90% of what was valuable to me was that I had nothing to do with communicating to people through email, spending more time on my content actually returns more value than 10-100 conversations I might have had back in the days of email. I like that comparison.

Yeah.

On one side, it was like, “How am I going to tame this?” and on the other side is like, “Wait a second. Why do I need to tame this? I’m a content creator,” in his case, he was just a content creator.

Yeah. It reminds me of Dan Kennedy, who doesn’t have any email or way you can reach him other than fax.

Yeah.

It cracks me up! I mean, he’s an old-school guy. He’s really old-school-you can only fax him.

Yeah. Well, this notion that everyone should be reachable by anyone at all times is very arbitrary once we step back so we should have more diversity. If there’s anything that catches my attention is, why we have too much lack of diversity in a work culture. I mean, the fact that almost every knowledge worker once or day have their inbox, it shouldn’t be the case. There’s such a diversity of different types of jobs and roles in knowledge work-why is everyone’s work day look the same? Same thing-why should it be the case that everyone in the economy just has this universal reachability? It just doesn’t make sense. I mean, if I ran Google, the very first thing I would do would say, “Every single of our developers, turn off their email accounts, get rid of it.”

Yeah.

And then we’ll just work backwards from there. They’re going to be problems probably, but let’s measure. I still think they’re going to produce better code if we can’t interrupt them, and we can figure out the rest later. Why don’t we have more diversity like that in our work culture? I think right now things are way too homogenous. I mean, everyone works the same way, we all have the same expectations and reachability, and it doesn’t make sense.

Yeah. My last question for you is, how is it that this makes sense for a computer scientist or a professor to be coming up with this new way of working-this old way of working-what’s the connection between this book and your older book, So Good They Can’t Ignore You? How does all that tie in?

Right. Well, in terms of the computer scientist, working on the type of questions I’m working on now, there’s sort of a philosophical and practical answer. The philosophical answer is, who better to write about the intersection of digital technology and work in satisfaction than someone who’s actually at the cutting edge of digital technology? I’m sort of well-suited to comment on this world that I’m a part of, and what’s its impact on the world I work. The practical answer? It just makes me much better at my job.

Right.

My job is, I’m a theoretician. I solve theorems for a living. This is what I do. I make a living by solving theorems. The better I am at doing deep work, the better I am at my job so the sort of practical, honest answer is, I first got really interested in deep work and optimizing deep work skills because it makes me better at my job. To give you a clear example of that, I mean, I’ve always prioritized the work, but during the year I was writing the book on deep work, I was particularly attuned to my deep work habits because just writing about it was exposing me to a lot of ideas, and it was also clarifying my thinking on what type of habits are more productive than others. During this year in which I was writing the book, Deep Work, my productivity as an academic should have gone down because I have a fixed amount of time, and I was taking a non-trivial fraction of it, and dedicate it to writing the book so I should have had less time to produce, but because I was optimizing my commitment to deep work during that year, my productivity, as measured by number of peer-reviewed publications at elite venues, was a factor of two larger than any previous year in my history as an academic.

Wow!

And that’s the power of deep work. It’s really not about that it will be nice to be a little less distracted or kids these days spend too much time on Facebook, but what is really about is, it can double the amount of academic papers you publish in a year that you have significant other time constraints. I mean, it’s 10x type improvement of productivity if you really commit to focusing intensely, and training that, and protecting that it’s not nibbling around the edges. That’s really the practical answer. It’s what helped me get tenure, in some sense. Looking back and connecting the dots, also, I guess it makes sense that, as a computer scientist, I’m writing about the impact of these technologies. In terms of how it connected to my last book, my last book argued that following your passion is bad advice.

The core idea was that, we don’t have a lot of evidence that most people start with a pre-existing passion, and we need to stop telling people that. Of course, you have a pre-existing passion, and it’s just about whether or not you have the courage to follow it. If you study the literature, and if you study people who are actually passionate about their work, the equation tends to be flipped. Passion is something that arises as later in your career-as you get good at something, as you make more impact, as you get more autonomy, as you make more connections to people, and as you get more time to your professional community, your passion for your work rises, your passion follows you, and you don’t start with it. The key, it turned out, to cultivating passion in your work life was, if you can get really good at something valuable quickly, you are going to develop passion for your work also much more quickly.

The natural follow-up question to the book was, “Okay, if I buy that, how do I get good at something really quickly?” and the answer was, deep work, so in some sense, this book was also a companion to that first book. The first book made the argument “You need to think about passion as something you’re pursuing, not that you’re following,” and Deep Work is saying, “Okay, here’s one way to get there,” so deep work, not only is going to be more productive, it’s not only going to give you this 10x increase to your perceived productivity, it’s also a core skill for developing true passion and sense of satisfaction your work so it really has a lot going for it.

Yeah. Love it! All right, thank you much, Cal! This has been mind-expanding and awesome. If somebody wanted to take the next step, learn more, and make some significant changes to their lives and their business, and apply deep work principles, obviously, they would need to get the book, but what else would you recommend for them to learn more? Do you have any kind of online training or is there an audiobook version? Is there some sort of seminar that they could take?

Right.

Is there a consultant they could work with?

Right. If you’re interested in deep work, there is the book. You can get the audio version at Audible. I also have a blog so if you go to CalNewport.com, I’ve been writing in detail for years about deep work, and you can get a lot of glimpses into sort of habits and tactics and case studies right there on the blog. The one thing I’ll have to apologize about, but it’s because I’m committed to deep work is, I’m hard to contact. I’ve never had a social media account so you can’t be on there. I don’t have a general-purpose public email address so there’s not really a way that you can consistently contact me. You’ll have to let my writing and my interviews, in some sense, speak on my behalf, but that’s a reflection of a commitment to deep work. I mean, I’m hard to reach, but sort of, by design, and hopefully, I’ve convinced a few more of your audience that they too become harder to reach in the near future.

Yeah, I hope so. I, for one, will become more unreachable. All right, so thank you again, Cal, and thank you, listeners, for your rapt attention, and for applying these principles so I thank you in advance because now, you have to take this stuff and apply it. Until next time! I’m your host, Stephan Spencer, signing off.

Important Links

Connect with Cal Newport

Tools/Apps

Books

Previous Get Yourself Optimized Episodes