In this Episode

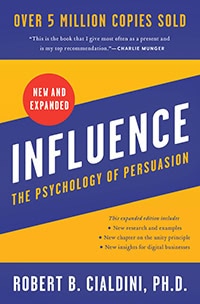

- [00:55]Stephan introduces Dr. Robert Cialdini, New York Times bestselling author of Influence and Pre-Suasion, both of which have sold over 7,000,000 copies in 44 different countries.

- [05:17]Dr. Robert talks about the viral video where a woman helped a blind man acquire more donations just by changing the words on his placard.

- [11:06]Dr. Robert recalls a time he worked at Opower, where the company helped reduce 3 billion pounds of Carbon Dioxide and saved $790 million dollars a year because of this business model.

- [16:04]Dr. Robert discusses other universal principles of influence.

- [21:25]How Warren Buffett has retained the trust of his shareholders by first admitting a weakness then mentioning their strongest features and comebacks.

- [26:36]How using the word, ‘but’ instead of ‘because’ can give you a powerful influence.

- [31:59]Stephan and Dr. Robert discuss ethical and unethical book launch strategies.

- [40:27]The reasons why ratings between 4.2 and 4.7 stars are more successful than five stars.

- [47:09]By asking someone’s advice instead of their opinion, you get a partner you’ve invited into the process of collaborating with you.

- [49:23]Visit Dr. Robert Cialdini’s website, be a part of the online Principles of Persuasion Workshop, and grab his latest book New and Expanded Influence to know how you can maximize the Principles of Influence.

Bob, it’s so great to have you on the show.

Thank you, Stephan. I’m looking forward to it.

First of all, I would love to hear what it is about influence that still excites you because clearly, you have a passion for it that has not waned in decades. What is it about it that keeps you excited?

There’s not a person I know who would not be interested to know how to become more influential.

I think it’s the universality of it. There’s not a person I know who would not be interested to know how to become more influential and also how to resist the appeals of those people who are trying to influence us in unwelcomed or undue ways. It’s both sides of the coin. I think everybody that I’ve talked to says, “Oh, yeah, tell me more about that because that’s likely to impact my daily interactions and even my effectiveness within those interactions.”

Right. It’s universally applicable whether you are a director of a company, a business owner, a new employee, a consumer, or a homeless person. It doesn’t matter who you are and what roles you play. You need to know about influence because you’re either on the influencing side, you’re on the being influenced side, or both.

Exactly. Let me just take up where you left off with the homeless person. There’s actually research to show how a homeless person could double the likelihood that someone will contribute to them when they ask for a donation on the street. It is to add the sentence, “of course, it’s completely up to you.” That more than doubles the likelihood that people will feel willing to do so because you’ve given them the responsibility of deciding in a way that’s very much also granting them the freedom to do so explicitly.

We can go all the way up to the top of the line. How does a leader do this—get people to say yes? One of the things that we found is that very often, the most effective communicators need to know when they are not the most effective communicator.

Peer-suasion; a more muscular form of persuasion.

They need to give the task to someone inside their organization who might seem more comparable to the individuals that they’re trying to move in that direction than the person at the top who might be seen as being too different from the average individual. People aren’t already interested in following that individual’s lead, but if we get in a team meeting, the manager is saying to somebody who’s already gotten on board with a new initiative, “Jim or Janet, can you tell me why you think that this new initiative that we’re pushing is the right thing to do?”

Now, those people who are hanging back don’t just hear from their boss. They hear from their peers. In this new edition of the book that you’re talking about, we have a whole section called peer-suasion which is a more muscular form of persuasion. You can harness that kind of strength of the principles of influence.

That’s so cool. I remember this video that went viral of a homeless person who had something written on a piece of cardboard. People were just passing him by. One lady came and wrote something different on the backside of it. She gave it back to the homeless person who incidentally was blind, so he didn’t see what she had written.

All the money just was flowing in. He kept hearing change thrown into his hat all day long because of the words. Then, she comes back later. He asked, “What did you write on this?” It’s really beautiful. I recall something about, “It’s a beautiful day. I, unfortunately, don’t have the eyes to see it, but you do”—something along those lines.

To be a successful long-term source of influence, you have to be ethical in every step along the way. You get the buy-in from people by building your credibility. Share on XYou’re very close. It was, “It’s springtime and I am blind.” All he had there was “I am blind.” Now, she says, “It’s springtime and I am blind.” People see the inequity there between what they are enjoying and what this man, unfortunately, cannot enjoy. Now, they seek to redress that inequity by giving some resources to him. Brilliant.

Really heartwarming and touching as well. If someone is trying to do good in the world, they’ve got a mission, they have a non-profit or something, and they want to inspire people to participate in this mission, in this movement—maybe donate, volunteer, tell their friends, and so forth—what are some of the best examples you found out there in terms of sparking this kind of a movement? What are some of the worst examples?

Let’s start with one of the worst examples. It’s that you’re not getting enough donations. You’re not having the success you want. What you say is, so many people are failing to recognize the importance of this cause and not donating to our mission. A serious mistake because you have just normalized the tendency not to give to this organization. You’re saying, most of the people around you like you aren’t doing this.

What our research shows is that when you tell people that the majority aren’t doing this—this is a regrettable thing that the majority of people are failing to do this—they take their cue from what the majority did. It’s called the principle of social proof. You decide what you should do based on what the people around you are doing. You never want to say that.

Here’s what I think you can do even if you’re not getting a lot of contributions. Even if let’s say you’re a startup organization or a new charity that doesn’t have a lot of traction yet, what we find is if you show a trend in the direction to where you are, even if it’s a minority, now, the minority status of that number—let’s say we’re only getting 20% of the people that we ask to donate or we’re only at 20% of what we think we need to be in order to be effective.

If you say that, you’re telling people most people don’t think it’s worthwhile, so what you get is less contributions actually, fewer contributions. But if you say, 6 months ago it was 10%, 3 months ago it was 15%, now it’s 20%. Now you get more contributions as a result because of a new kind of future social proof that you’ve established with that trend, future social proof.

There’s a human tendency to project a trend into the future. People will say, “Oh well, that means in the future, it’s going to be even more and more.” Eventually, the majority of people will be doing this. If you’ve got a good idea but it’s early in the process—maybe it’s a new product, a service, an idea, or a charity organization—and you don’t have the popularity yet that allows you to use social proof—the majority are doing this—you can use a trend toward the majority and get there much faster.

That’s amazing because when our brains extrapolate that we’re already pre-selling ourselves on the value of it even though it hasn’t arrived yet.

That’s right. Again, we want to be sure never to say only 20% are doing this because that’s going to cause people to be less likely to do it. But if you get there in a trend, it reverses the process. Now, you’re winning instead of losing with that 20%.

I recall that you shared an example, a study, of utility customers, whether it was water usage or electricity usage—something along those lines. Do you recall what I’m referring to?

Yes. There’s a company that I was the Chief Scientific Officer for a few years called Opower that had its business model. They would partner with utility or energy companies and send to all the customers of those companies, not just information that compared how much energy they were using that month compared to the previous month or the previous year from that month.

There’s a human tendency to project a trend into the future.

They said, instead, here is how you’re doing relative to your most comparable neighbors. The people who are close to you who have the same-sized home, who have the same air-conditioning and heating system, and have the same number of rooms. You can get all that information from census tract data. Here’s where you stand relative to them.

That has been a wild success in the 10 years that Opower has been in business. We have been able to reduce 3 billion pounds of carbon dioxide from being put into the environment by people reducing their energy consumption. Consumers have saved an average of $790 million a year by simply adjusting their consumption to that of their comparable neighbors who are doing better than them. It means that, well, if they can do it, I can do it. It becomes feasible to do this if you see that those around you (just like you) are able to do it.

That brings up another point that I just was floored by initially, but it made all the sense in the world in retrospect. That was the power of the mediocre or mildly impressive case study.

I learned about this from one of my coaches, James Schramko, who’s an internet marketer. He’s spoken many times at the Traffic and Conversion Summit. He’s spoken there as well. He talks about how if you gave a case study on your website, in a presentation, or whatever, that is lightyears beyond the audience’s present state or where they’re even seeing themselves in the future.

You can use a trend toward the majority and get there much faster.

I had a client, Chanel, that did this and that. They were able to get this kind of result in Chanel. I’m not Chanel. I’ll never be Chanel. That’s ridiculous. Their brain essentially shuts off for the rest of it. The mildly impressive case study is one where it’s like, we got 30% growth in the course of a 12-month time period and went from X to Y. Thoughts on that?

You’re exactly right. You’re hitting right on the bull’s eye of comparability. If those individuals are like you, then you start taking their experiences in and comparing them to your own. If somebody’s way beyond you, even though there’s a tendency for communicators to want to present the most positive face on what they’ve been able to accomplish, by doing that, you’re shutting down the tendency of the people who you’re speaking to to see a connection to themselves, so they don’t really process that information deeply as a result or accept it as relevant to them.

Very true. Now, let’s talk about the line where ethical influence ends and fabricated or unethical influence begins. How do you know where that line is, whether you are on the delivering side or on the receiving side?

This is such an important question because it seems to me that to be a long-term successful source of influence, you have to, from the beginning, be ethical in every step along the way so that if you do get the buy-in of the people and you don’t want to step over that line because if they see you as having an intent to deceive them with these approaches, you just crash in terms of your credibility. What’s the differentiator?

I claim there are seven universal principles of influence that move people in your direction. We’ve already talked about one of them, social proof. If a lot of people like you are doing this, it’s probably the right thing for you to do.

Another one is authority. If the experts are doing this, then you’ll probably reduce your uncertainty of what you should do in that situation because the knowledgeable people are urging this particular step. Here’s another one, which is scarcity. If what you have is scarce, rare, unique, or dwindling in availability, if you tell people that they want it more. We want more of those things we can have less of.

Here’s the differentiator between influence and manipulation. You’re a successful influencer if you point to something that’s truly there. Do you really have social proof? Do you really have a popular approach, a lot of a trending influence in your direction? Do you really have the voices of legitimate authorities who can speak to the direction that you’re asking people to take? Do you really have a unique uncommon feature of what you have to offer that nobody else can provide?

Simply pointing to those things is entirely ethical. Not only is it ethical, I think it’s commendable to do that. It’s not only not objectionable, it’s commendable to inform people of what the true sources of influence that typically steer them correctly are in that situation.

The unethical person is the one who fabricates that popularity, claims it by lying with statistics or just outright lying, choosing a voice of somebody who’s not really an expert on the topic but implying that this person is. Claiming that this is our last product, our last model, or our last item when it’s not. There are others in the storeroom. You’re just getting people to choose it because it’s the last one. That’s the difference.

An unethical person is one who fabricates popularity.

Do you point to something and thus, educate people into a cent, or do you trick them? Do you deceive them into it, a cent? That’s the differentiator.

I’m also thinking about times where there’s information asymmetry and it’s just selectively chosen which things to share with you like. If you’re a car salesperson, you’re not going to share that, “Well, this had an accident and it’s repaired now” and so forth unless you’re specifically asked perhaps. Hopefully, they will volunteer but many probably would not.

Then there are aspects that are very favorable that are being immediately shown. Well, let me show you this, that, and the other thing from our invoice or whatever. This is the information that is favorable, but the stuff that’s not, they might call it a white lie because they’re omitting things. I actually think it’s a brazen lie to withhold that information.

I’m on your side on this one. I’ll tell you why I think you’re right, not just in terms of the morality of being sure people are properly informed about both sides, but because it turns out to be more effective. If you mentioned a weakness in your case early in your presentation so that people have been informed that you are not only knowledgeable about the topic—you know the pros and the cons—you’re trustworthy enough to describe the cons as well as the pros.

The principle of social proof is deciding what you should do based on what people around you are doing. Share on XStephan, that’s the moment after you have admitted a weakness to mention your strongest argument, your most compelling feature, your most attractive aspect of your case because people now view the next thing you say as coming from a credible communicator. If you never mentioned that weakness, they wouldn’t know that about you, or if you buried it at the end of your presentation, which is what most people do. First of all, they present all of the strengths, and then at the end, they might mention a weakness.

Let’s say you’re a financial advisor and you want somebody to move in a particular direction. You tell them all the strengths of this and then at the end, you say, but of course, there are tax consequences. This may take a little bit longer to show a profit than some of the other things we’ve been considering. If you mentioned those things first, and then you just say, but here are the things that I am enthusiastic about in there, why I’m recommending this despite what the weaknesses may be, those strengths now become perceived as something people process more deeply and believe more fully.

Warren Buffett does this every year in the letter he sends to his stockholders for Berkshire Hathaway, his amazingly effective company. On the first or second page of his report to shareholders, he mentioned something that went south that year, something that didn’t go according to his hopes. He says, “But we’ve learned from this, and that will never happen again.” Now, let me tell you all the things that went right. I’ve been getting his reports for over 20 years now. Every time he does it, I say to myself, wow, this guy’s a straight shooter. He’s coming up with this thing that went wrong.

Normally, a CEO buries it in some footnote on page 43. No, this guy’s upfront with us. What’s the next thing he’s going to say? Then he talks about all the strengths. Because of that, I have never sold the single share of Berkshire Hathaway stock that I received 25 years ago as a gift. It was a gift. It was from his partner, Charlie Munger, who sent it to me. He said, “Your book has made so much money for us by one of your principles called the Principle of Reciprocation that says we have to give back to those we have given to them, you are owed this.”

It was worth $75,000 25 years ago. Today, it’s worth $430,000, and I never sold it even when I had doubled and tripled and quadrupled my profit because every year, Warren Buffett would convince me about the strengths of the case for Berkshire Hathaway by first mentioning a weakness in that case.

That is so smart. I love that. What a great example. Now if I were to pitch you to be on this podcast and I would start with a weakness—now, you said yes, without me doing this. If I had said, “You know, we’re not very popular in terms of podcasts. The number of downloads isn’t very impressive, to be frank. But I have had guests like Tim Ferriss, Dave Asprey, Jay Abraham, and so forth.” Then that would potentially be more influential and persuasive than if I had just simply launched in with, “I’d love to have you on my podcast, and here are some of the guests.”

I’m not ready to accept all of the positives until you’ve shown me your credibility. I’m not open to them, they’re bouncing off me. Even your strongest arguments might bounce up because I don’t know whether I can trust what you’re saying. If you tell me something that’s true, that’s a weakness in your case, I now trust the next thing you say differently. If you tell me about Tim Ferriss, well now, I go, wow.

The key to all of this is the word “but.” First of all, you never say here are all the things wrong with me in my podcast. You mentioned a weakness relatively early, not the very first thing you say to people. You mention that, and then you say, “but,” “however,” or “nonetheless.” That’s a bridge into your strengths.

The key to all of this is the word “but.”

I have a friend who’s a psycholinguist. She studies the psychology of language. She said, “Do you know what the word but signifies in every human language? Take what you just heard and put it away and focus your attention on the next thing I’m going to say.” Can you see why we want our weaknesses before the ‘but?’ That’s what you put away, and our strengths after the ‘but.’ ‘But’ tells us, now, focus here. That’s where the strength should be.

I advise people, do you want to know where to put your strongest argument? You put it in the moment after you’ve mentioned a weakness that your strengths can just sweep away.

To use this the wrong way would be, for example, to give a compliment to somebody and then the criticism after the but because they wiped out the entire compliment and all they heard was the negative commentary.

That’s right.

Now, if instead of the word but you use the word “because,” then you can get all sorts of powerful influence there too. You’re not going to use a weakness in that example, but you’re going to give a reason that doesn’t necessarily have anything to do with the thing you’re trying to get from them.

Well, there’s a new study that shows that, but of course, we want to give a reason that’s aligned with the direction we want people to go. The study that you’re talking about is a classic in behavioral science, in which researchers at Harvard University went to the university library, and they wanted to see what they could do to get people to allow them to skip ahead of them in line. In the control condition, they walked up to the people and said, “Excuse me. I have eight pages, can I skip ahead of you in line?”

The most effective communicators need to know when they are not being the most effective communicator. Share on X60% of the time they were successful. If they said, “Excuse me. I have eight pages, can I skip ahead of you because I’m in a rush,” now they got 94%. But here’s the key, if they had a third condition, they walked up and said, “Excuse me. I have eight pages, can I skip ahead of you, because I have to make some copies?” I have to make some copies is not any new information. Everybody in that line has to make copies. 93% say yes.

It wasn’t the reason, it was the word because that foretold a reason that was about to follow. When people heard the word because, they thought, okay, here comes a reason. People want reasons in order to say yes to things. You’re exactly right. If we foretell the reason that’s about to come with the word because, people become attuned to the next thing you’re going to say. Once again, they focus their attention on the next thing you’re going to say, and if you’ve got a good reason there, you go from 60% to 94% in this particular situation.

I love that study, it’s so good. Now, I don’t know if you’re familiar with Jay Abraham. Are you guys friends perhaps?

We’re not personal friends, but I certainly know and respect his work.

He’s great. One of his principles is the principle of preeminence. If the prospect is better served by being sent elsewhere, then it isn’t just your ethical responsibility, it’s good business to send them to your competitor. I’d love to hear your analysis of this from the Influence and seven principles perspective.

It is credibility again. The principle of authority and the most powerful kind of authority influence that you can be is one who has credibility in the eyes of the prospect. That means you are knowledgeable and you are trustworthy.

Well, by saying, “We’re not right for you, here’s a better option for you,” you have just established yourself as knowledgeable and trustworthy. The key is, the next time that person needs something other than what they’ve gotten from the rival, they’re going to come to you first because you have established yourself as a source of information that they can believe explicitly.

Now, you’re in a position to make recommendations for things that they don’t even—if you do say, “Now we do have exactly what you need, we can really help you.” They don’t ever think about going toward a rival. You’ve already closed the deal. Weeks before, months before, you’ve closed the deal.

There’s the ancient Chinese military expert, Sun Tzu, who said, every battle is won before it’s fought. It’s what you do first. What Jay was saying, you can do something months ahead of time, and you’ve won a battle that has yet to be engaged. At that point, the next time you give them a recommendation they’re going to believe it. They’re not even going to think about going elsewhere now.

That’s awesome. I love the book, The Art of War by Sun Tzu. My favorite quote from that book is, “Tactics without strategy is the noise before defeat.”

Right, me too. I love that one.

Now, speaking of books, you have a very impressive number of books sold for both of your books. I’m curious what your thoughts are about ethical and unethical book launch strategies because I have many friends who have book launches, either coming up or in progress right now. I’m going to have some books launching here in the next year, probably three of them. I would love to hear the best of the best examples and some of the cringe-worthy examples that you couldn’t believe actually worked but shouldn’t have.

Every battle is won before it’s fought.

Certainly, the best of the best is again to take Sun Tzu’s advice and establish your credibility before the book is ever launched. You do that by getting known experts, legitimate authorities on the subject of your book to write endorsements of it for the cover, the back, the inside pages, so that when people review those experts’ opinions in the launch on the cover of the book, or when the launch occurs, they see that I can reduce my uncertainty about whether this is a good book because so many experts are saying it is. That’s certainly one way to do it.

Another way to do it, and I’ve done it with this new edition of Influence that just came out. We added 220 pages to the previous edition. What did we label this? Not revised, new and expanded. People recognize that they were going to get novel information here that wasn’t in the previous edition. It was greatly expanded beyond the previous edition, not just new, but a lot more information than they had in the previous one.

Finally, because we had already sold five million copies of that book, the earlier versions of it, we were insistent with our publisher. You need to put that on the cover of the book, it’s social proof. It’s not just the experts who are on the back of the book endorsing it, it’s people like potential readers, just like the people we want to move in our direction for this one. Five million people have done it. As you mentioned in your introduction, in 44 different languages.

It speaks to the fact that these are universal kinds of insights into the human condition. If we can get that many people from that much of a diverse set of countries wanting the information. Those were the things that I did. Here’s one of the things that I had to fight for in order to get a previous edition. By that time we had sold—it was the third edition—three million copies of the book. By the previous edition, it was like 1.5 million.

Don’t take out the crucial thing that is a lever of influence.

They didn’t want to put the new number on there, and I had to fight and fight and fight. They said no, no, we need that space for the design of the cover. It’s important that we do not have too much information. Too much information? This is crucial information. Take something else out.

They needed white space. This is what designers do. They need to have enough space in there, so it’s a welcoming image for people that are looking, but you don’t take out the crucial thing that is a lever of influence that’s in the book as to what you should do. Those are the kinds of battles you have to fight.

What’s an example that you know of from other book launches where it’s a little bit cringe-worthy with what they did?

They use as endorsers of the book, what we call “blurbers.”They put people who are associates of theirs. Of course, we’re friends of theirs, not independent voices in this. You say, well, come on, that has to do with something else than the quality of the material. It has to do with the quality of the relationship you have with the person who’s endorsing it.

Well, I have asked friends to write book blurbs for me, famous friends, and I’ve asked people who barely know me to write blurbs. I just never thought twice about the difference between those two. I just threw them all in the same pot and then put them into the front matter of the book or the back cover and like, yeah, there we go.

Do you know what I’ve seen? I’ve actually advised a friend of mine. He showed me this list of endorsers, two of whom said, “Not only do I have a lot of experience with X, the author (let’s say his name is Jim, it wasn’t), he’s a friend of mine.” What? It’s in the blurb? There’s a reason for this praise that doesn’t necessarily have to do with the merits of the presentation there? It has to do with friendship? Take that out. Ask that person to take out that line about friendship. It corrupts the independence of the judgment.

Do you think it’s unethical to include the blurb at all because of the friendship?

No, I don’t think it’s unethical. If anybody knows about the friendship, it’s suboptimal to do it.

Got you. What do you think about—I don’t even know what they call them, it’s not a marketplace, but it’s more like a community of people who get paid for free products for giving an Amazon review?

I think that’s trouble. I know that now there are more and more restrictions that have to be announced for influencers, for example, who use a particular product or present it on their blog. They have to transparently say, I’m being paid to do this by this or I’m being given this. Otherwise, it becomes unethical, I think, because of that other source of influence besides the quality of the thing, the thing that’s on offer.

You're a successful influencer if you point to something that's truly there. Share on XI think it’s unethical. If someone’s getting paid in free product, cash, gift cards, or anything, that’s slimy in my opinion. If someone is also faking Amazon reviews, that’s even worse. That’s a whole other level. It happens a lot. There is so much fakery going on and manipulation with Amazon sellers.

Amazon is constantly trying to develop algorithms to detect and delete those kinds of fakes, but it’s not always possible because the fakers are getting more sophisticated. Here’s a fascinating result that I saw as it applies to how influences are employed in online platforms. Everybody looks at star ratings. Do you know what ironically is not the most successful star rating to create a conversion? Five stars are not.

Got you.

It turns out the most successful is a range between 4.2 and 4.7 stars. Below 4.2, you say, well, maybe this isn’t such a great product. Above 4.7, you say, well, maybe this isn’t all legitimate. Maybe there’s fakery in here. One of the things I’m happy with in the reviews of the new book is that we’re at 4.7 right now. The ones who are saying 3 or 2 stars, the reasons they’re giving are great.

Five stars are not the most successful star rating to create a conversion.

They’re like, “Oh, well, the book arrived damaged.” “I didn’t like the font size.” Okay, well, good, all right, those are legitimate concerns and they should be registered, but they don’t undermine. I think if you ever do get a negative review on your site, you should always respond to it. Now, it doesn’t have to be in a confrontational way. You can always respond to it and say, “Well, I’m sorry, you’re you feel that way, but”—there’s your but—”I’m so glad that the great, great majority of reviewers have not felt that way.”

What about the advice that many, many internet marketers give to not feed the trolls? Don’t give them any further attention when they’re dissing you in a YouTube comment or a blog comment.

I think that’s correct if you’re going to be confrontational because what that does is get their backs up. They love that. They love to be involved in an exchange with somebody famous. No, you’re conciliatory. You say, “I’m sorry, you felt that way, I’m so glad that the great majority of people don’t.” What are they going to say to that? They’ve seen it. The great majority of people don’t. Now you’ve got social proof and credibility on your side.

Got you. Now, what is your opinion on online reputation management? It’s a form of manipulation, in a way, because you’re pushing negative commentary off of page one on Google. It’s a form of SEO in that way, but it’s also stacking the deck in your favor without letting people immediately see the detractors or the negative commentary. Is that ethical, unethical? Does it depend on whether it’s a legitimate organization or person? What’s your view on that?

Do you want to know where to put your strongest argument? You put it in the moment after you've mentioned a weakness that your strengths can just sweep away. Share on XI think it’s less than ethical. You want to be as transparent as possible, but you always want to have something to say to those individuals. I know some of them may be trolls, but you can disarm them by saying the thing that we talked about a minute ago, or saying, but the evidence isn’t in your favor in that regard because X or Y. You always should have something to disarm them rather than to confront them, dismiss them, or derogate them. It should be evidence-based or something. You can say, I’m sorry, you feel that way, but I noticed that very few people feel that way.

Good point. I know there’s a principle that you call unity. I didn’t really get the impact of that until recently. I heard you present on Genius Network or was it Metal? I forget which one. Anyways, I heard you present, it was phenomenal. You gave some examples of unity and action and how persuasive that is. I’d love for you to share a little bit of this for our listener.

Let me give you a personal example and then a more general one. A few years ago, I was writing a report that was due the next day. As I was reading over it, I saw that one section of it was weak. It didn’t really have the evidence I needed to clearly make a compelling case for what I was claiming. But I knew a colleague of mine in the psychology department where I work who had done some research the year before, and he had the data in his archives.

You want to be as transparent as possible.

I sent him an email and I said, “Tim” (it’s not his real name). I explained, “I have this thing, it’s due tomorrow. I don’t have the data, I know you do. Could you go to your archives, could you get out the data, and send them to me today so I could get this report done on time? I’m going to call you and ask you to do that and give you some of the specifics of what I need.” So I called him. He said, “Bob, I know why you called, and the answer is no. Look, I can’t be responsible for your poor time management skills. It’s due tomorrow, but so what? I have things due tomorrow too. Why would I prioritize yours over mine?”

If I hadn’t read the stuff about unity that says, we say yes to those people who share important categories that define our identity with us, people who are one of us. We just say yes to those people. If I hadn’t seen that research, I would have said, “Come on, Tim, I need this, it’s due tomorrow.” He had already said no to that. I said, “Come on, Tim, we have been in the same psychology department now for 12 years. I really need this, and I had the data that afternoon.”

He had to say yes, I was of him. I was a member of the psychology department. How many fellow organizational companies or family members can we just say, we’ve been together now for a long time, I really would wish you to do this for me. Now, here’s the general example. Suppose you’ve got a new initiative, you want the buy-in of the people around you so you can move that initiative up the ladder and you want to ask for their input on your new idea and get their buy-in for it.

What we typically do is give them an outline of our idea or a blueprint of it and say, “Can you give me some feedback on this?” It’s fine to ask for their input. It’s great, actually. But the word you should use to ask for their input is not the one we usually use. We usually say, “Can you give me your opinion on this?” Here’s the truth. When you ask for somebody’s opinion, you get a critic. Instead, if you change one word and ask for their advice instead of their opinion, now you get a partner.

You get someone you’ve invited into the process of collaborating with you on this process. The research shows, if you change that one word, they see themselves as with you now on this because you’ve asked for their advice, you asked them to collaborate with you on it. What you get is a significantly more positive response to the very same idea if you ask for advice about it versus opinion. Even from the most recent research I’ve seen, even if you ask for feedback, you don’t get as positive and as helpful a response.

I would have guessed that feedback would have been critical as well. Counsel, on the other hand, I would think would be like advice. It would be asking them to (in a sense) partner with you on it.

I haven’t seen the research on that. I don’t think there has been anybody who’s done that research, but I bet you’re right.

Amazing. I know we’re out of time. I wanted to be sure our listener knows where to get your book and more materials, perhaps some videos of you speaking and so forth. I’m sure there’s got to be some great stuff on YouTube, on your website, and so forth. Where do they go to learn more from you, besides, of course, Amazon to pick up the book?

Well, you’re right about our website. It is influenceatwork.com. There we’ve got access to information about our books, speaking opportunities, and training. We even have a brand new on-demand online Principles of Persuasion Workshop that people can subscribe to if they want to learn about effective and ethical influence, that’s available there too.

Of course, the choice is up to you.

Yes. It’s completely up to you, but influenceatwork.com awaits decisions.

Perfect. I love what you’re doing out there in the world. You’re making people aware of influence, using it ethically, and also knowing when it’s being used on them unethically. You’ve got just a lot of great karmic brownie points accumulated, I’m sure, for all this great work.

Thank you. I appreciate hearing that.

Thank you, listener. Now, go out there and make a difference in the world using positive influence techniques. We’ll catch you in the next episode.